Ancient, primordial helium that was forged in the wake of the Big Bang is leaking from Earth's core, scientists report in a new study.

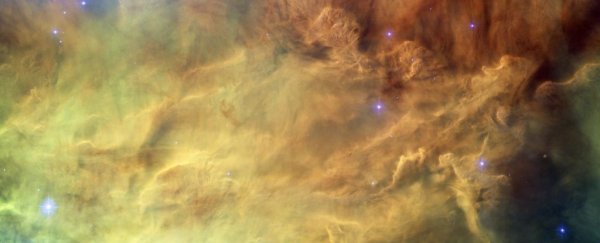

There's no cause for alarm. Earth isn't deflating like a sad balloon. What it does mean is that Earth formed inside a solar nebula – the molecular cloud that gave birth to the Sun, a detail about our planet's birth that has long been unresolved.

It also suggests that other primordial gases may be leaking from Earth's core into the mantle, which in turn could yield information about the composition of the solar nebula.

Helium on Earth comes in two stable isotopes. By far the most common is helium-4, with a nucleus containing two protons and two neutrons. Helium-4 accounts for around 99.99986 percent of all the helium on our planet.

The other stable isotope, accounting for just about 0.000137 percent of Earth's helium, is helium-3, with two protons and one neutron.

Helium-4 is primarily the product of the radioactive decay of uranium and thorium, made right here on Earth. By contrast, Helium-3 is mostly primordial, formed in the moments after the Big Bang, but it can also be produced by the radioactive decay of tritium.

It's the Helium-3 isotope that has been detected leaking out of Earth's interior, mostly along the mid-ocean volcanic ridge system, giving us a pretty good indication of the rate at which it escapes the crust.

That rate is about 2,000 grams (4.4 pounds) a year: "about enough to fill a balloon the size of your desk," explains geophysicist Peter Olson from the University of New Mexico.

"It's a wonder of nature, and a clue for the history of the Earth, that there's still a significant amount of this isotope in the interior of the Earth."

What is less clear is the provenance; how much of the helium-3 might be emerging from the core, versus how much is in the mantle.

This would tell us the source of the isotope. When Earth formed, it did so by accumulating material from the dust and gas floating around the newborn Sun.

The only way significant amounts of helium-3 could be inside the planetary core is if it were formed in a thriving nebula. That means, not at its outskirts, and not as it dissipated and blew away.

Olson and his colleague, geochemist Zachary Sharp of the University of New Mexico, investigated by modeling Earth's inventory of helium as it evolved. First, as it formed, a process during which the protoplanet accumulated and incorporated helium; and then after the Great Impact.

This, astronomers think, is when an object the size of Mars smacked into a very young Earth, sending debris flying into Earth's orbit, eventually recombining to form the Moon.

During this event, which would have re-melted the mantle, much of the helium locked inside the mantle would have been lost. The core, however, is more resistant to impact, suggesting that it could be quite an effective reservoir for holding onto helium-3.

In fact, this is what the researchers found. Using the current rate at which helium-3 is leaking from the interior, as well as models of helium isotope behavior, Olson and Sharp found that there are likely 10 teragrams (1013 grams) to a petagram (1015 grams) of helium-3 in our planet's core.

This suggests that the planet had to have formed inside a thriving solar nebula. However, several uncertainties remain. The likelihood of all the conditions being met for the sequestering of helium-3 in Earth's core are moderately low – which means that there may be less of the isotope than the team's work suggests.

However, it's possible that there is also abundant primordial hydrogen in our planet's core, caught up in the same process that may have accumulated helium-3. Looking for evidence of hydrogen leakage could help validate the findings, the researchers say.

The research has been published in Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems.