Prions are the misfolded versions of the prion protein that can attack the brain from the inside and cause a variety of neurodegenerative diseases, including Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD). Now a new study makes them even scarier than before: they can lurk undetected for 30 years before attacking.

That's based on the latest research from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the US, which found evidence of one patient who didn't develop CJD until 2015, even though the initial exposure was thought to happen in 1985.

That's the longest latency period for a prion-related disease that we currently have on record, but other cases could turn up that beat even that, according to the researchers from the CDC and several medical institutions in Japan.

"It is possible that there are some undeveloped patients of acquired CJD because of long latency periods, and they may die without CJD onset," one of the researchers, Ryusuke Ae from Jichi Medical University in Japan, told Ed Cara at Gizmodo.

"So far, the latency periods are only known by God."

Before the problem was spotted and sterilisation methods were improved in 1987, CJD could be caught from contaminated grafts of dura mater, a tough membrane used to heal the brain after surgery. In particular, a graft brand known as Lyodura was identified as infecting brains with abnormal prion proteins in Japan.

Because we know when these grafts were applied, we can work out how long the prions remained dormant. The latest study looked at 22 new cases of dura mater graft-associated CJD (dCJD) identified in Japan since 2008, adding to an existing set of 132 identified since 1975.

Between 1983 and 1987, some 20,000 people received a Lyodura graft in Japan each year, around fifty times more than the number in the US during the same period.

While Lyodura cleaned up its processes to avoid contamination in 1987, the grafts weren't actually banned in Japan until 1996 – so we could be looking at more cases of dCJD coming to light in the future.

And the researchers advise that more work needs to be done to identify potential pockets of prion disease so they can be dealt with: strict donor screening, comprehensive record keeping, prevention of cross-contamination, and the use of proven sterilisation methods are all needed, they say.

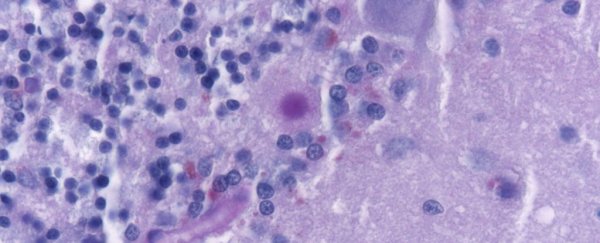

Once prions become misfolded, they quickly turn into contagious pathogens, recruiting other prions and destroying the brain piece by piece. Based on what scientists have learned about prions, they think diseases like Alzheimer's and Parkinson's might also involve contagious proteins.

A very rare disease called Kuru, similar to CJD and also caused by prions, could have an incubation period of 50 or 60 years, based on studies of a tribe of cannibals in Papua New Guinea. In this case though, it wasn't contaminated grafts that passed on misfolded prions – it was eating the brains of dead tribespeople.

While that's something most of us can refrain from doing, the long latency periods that have been observed in the tribe suggest we can't let our guard down when it comes to prion diseases and CJD. In the end, research like this might lead to a much-needed cure.

"Maintaining surveillance for CJD is essential to assess whether longer-term patients present in the future," Ae told Gizmodo. "It may also help the research that can delay the onset of disease."

The research is available to view on the CDC website.