Bacteria are outmaneuvering antibiotics faster than we can develop the drugs, and so scientists have turned to the human gut – a competitive environment, home to some 100 trillion microbes – to look for ingredients to use in fighting disease.

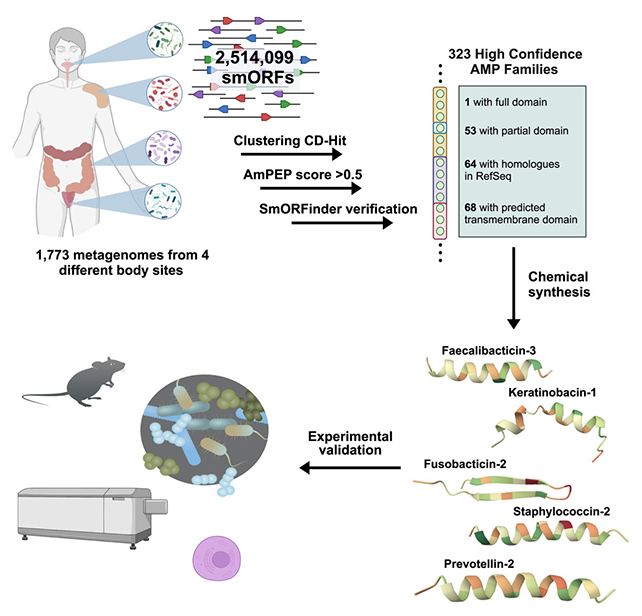

Researchers in the US looked at gut microbiomes from 1,773 people, analyzing 444,054 previously identified proteins for antibiotic potential.

Of the 78 most promising candidates that the team synthesized and tested in the lab, 70.5 percent of them showed the ability to fight off microbes such as bacteria, indicating they could eventually be used in antibiotics – and suggesting our guts do indeed harbor a wide selection of bug-fighting substances.

"We think of biology as an information source," says bioengineer César de la Fuente from the University of Pennsylvania.

"Everything is just code. And if we can come up with algorithms that can sort through that code, we can dramatically accelerate antibiotic discovery."

One of the most promising proteins discovered, prevotellin-2, showed bacteria-busting abilities that matched polymyxin B – currently one of the leading antibiotics deployed for infections that have developed resistance to multiple other drugs.

"This suggests that mining the human microbiome for new and exciting classes of antimicrobial peptides is a promising path forward for researchers and doctors, and most especially for patients," says physician-scientist Ami Bhatt from Stanford University.

There's a lot of work ahead in being able to convert these proteins into actual working antibiotics, but these early results are very promising – and even more so if they're comparable to the 'drugs of last resort' that are already in use.

The researchers also note that the identified proteins are not built like conventional antimicrobial molecules. That could perhaps open up whole new ways of developing these superbug killers.

"Interestingly, these molecules have a different composition from what has traditionally been considered antimicrobial," says bioengineer Marcelo Torres from the University of Pennsylvania.

"The compounds we have discovered constitute a new class, and their unique properties will help us understand and expand the sequence space of antimicrobials."

The traditional way of developing antibiotics from the wider environment takes a lot of time and effort – which is why de la Fuente and his colleagues are looking for sources of antibiotics already in nature that can be activated more quickly.

And they are very much needed, too: antibiotic resistance is a fast-growing problem, not helped by the way we're treating the planet, and it has already been linked to millions of deaths. Scientists are working hard on solutions, but it's a constant race to stay ahead of the ever-evolving bacteria we're fighting against.

The discoveries reported here back up the original hypothesis of the researchers: that having to constantly evolve and adapt in the gut in order to survive could well give our microbiome the tools to kill off other infections with targeted drugs.

"It's such a harsh environment," says de la Fuente.

"You have all these bacteria coexisting, but also fighting each other. Such an environment may foster innovation."

The research has been published in Cell.