Mosquitoes are normally associated with spreading malaria rather than preventing it, but in a new study scientists have used the insects to administer a promising new vaccine that could offer much better protection against the disease than current options.

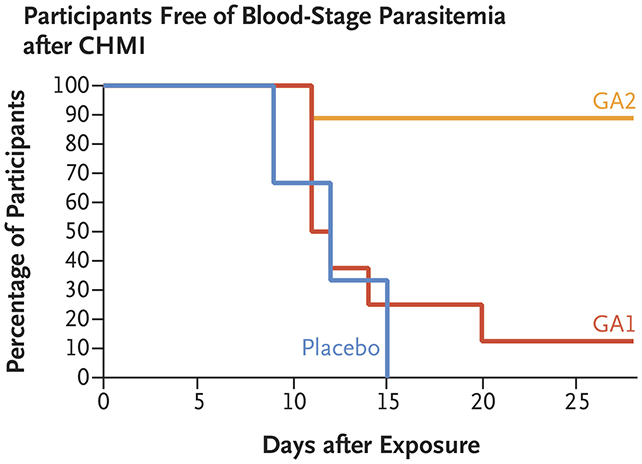

It's the second generation of this particular vaccine type, and the improvement shown in this study is significant: eight out of nine young adults given the new vaccine were protected against malaria, compared with one out of eight given the existing one.

The new vaccine, developed by researchers from Leiden University and Radboud University in the Netherlands, uses a genetically weakened version of the Plasmodium falciparum parasite that causes malaria in humans. This version (GA2) doesn't trigger malaria, but does prepare the body to guard against it.

"These crippled parasites are administered through a mosquito bite and reach the human liver as usual," says vaccinologist Meta Roestenberg, from Leiden University. "But because of the gene turned off, this parasite cannot complete its development in the liver, cannot enter the bloodstream, and thus cannot cause disease symptoms."

"Meanwhile, this crippled infection does create a strong immune response in the liver, which can protect the person from a real malaria infection in the future."

Having the parasite take longer to develop in the body seems to help: with GA2, P. falciparum takes almost a week to mature inside the liver, compared with 24 hours for GA1, the previous version. That gives the immune system more time to recognize what it is, and work on fighting back.

The GA2 vaccine triggered a bigger and more diverse set of immune cells, the study showed, which may help explain its much improved effectiveness. Understanding why it works so well will give researchers a better idea of how to further refine it.

Observed side effects were relatively minor, the researchers report, and mostly involved redness and itchiness around the mosquito bites. All participants were put on a course of anti-malaria drugs after the study data had been collected.

Progress continues to be made in tackling malaria, whether it's cutting it off at the source or protecting the human body. However, we're still seeing almost 250 million cases per year, and hundreds of thousands of deaths – and current vaccines only protect around 50-77 percent of the population, often for not much longer than a year.

As for the mosquito bite delivery system, this isn't particularly unusual for research like this: it's useful because it means the the modified parasite is delivered and targeted in the same way as the full-strength version, but it isn't practical to use the approach to actually roll out a vaccine to the public.

"In short, the test with our new crippled GA2 parasite performs very well," says clinical microbiologist Matthew McCall, from Radboud University.

"We now plan to test vaccination with similar GA2 parasites in real life."

The research has been published in the New England Journal of Medicine.