Proteins found on the surface of animal cells and in between them could be a target for drugs to stop Alzheimer's in its earliest stages, according to a new study.

The proteins – heparan sulfate-modified proteoglycans (HSPGs) – are involved in regulating cell growth and the interaction of cells with their environment, and have previously been looked at in relation to neurodegenerative disease.

Those links encouraged the US team behind the study, led by researchers from Pennsylvania State University, to investigate further.

The role of these proteins in healthy body functioning, including autophagy – the cell repair process that cleans out waste material, which is disrupted in certain types of dementia – makes them worthy of a closer look, say the authors.

"Strategies to treat Alzheimer's disease to date have largely focused on pathological changes prominent in the late stages of the disease," says molecular biologist Scott Selleck, from Pennsylvania State University.

"Drugs that affect the earliest cellular deficits might provide important tools to stop or reverse the disease process."

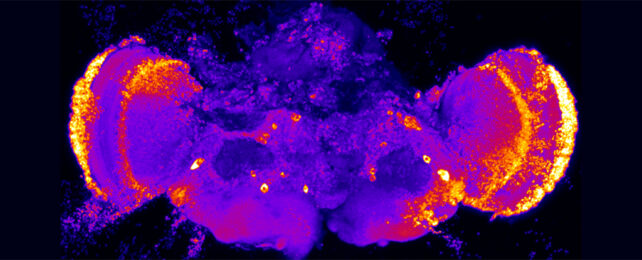

In tests on genetically modified fruit flies, mouse brain cells, and tissue derived from human cells, the researchers observed disruption in the key processes HSPGs are involved in. As well as autophagy, those processes include cell energy production, and the buildup of fatty compounds known as lipids.

When the team made certain tweaks to the way HSPGs function, some of the dementia-related damage was reversed. Cells got better at repairing themselves, and neuron death was halted.

What's more, when the human cells were blocked from producing chains of heparan sulfate, it affected more than half of the approximately 70 genes linked to the latter stages of Alzheimer's. The thinking is that HSPGs could play a role at different stages of disease progression.

This research is still in its very early stages, and these connections are only just beginning to be identified – further down the line, much more research would be required to develop drugs that interact with HSPGs to treat Alzheimer's. However, it looks like another promising avenue for experts to explore.

"Targeting the enzymes that make heparan sulfate could provide a means of blocking neurodegeneration in humans," says Selleck.

There are thought to be more than 55 million people living with dementia globally, a number that's expected to double in the next 20 years. Each piece of research like this gives us renewed hope that we'll find effective treatments sooner rather than later.

Part of the difficulty in finding treatments for Alzheimer's – the most common cause of dementia – is that we're still not fully sure what triggers it, with a combination of factors likely responsible. Recent research has looked into aging brain cells and the multiple ways that inherited genetics could play a role.

"We are interested in understanding the earliest cellular changes that are found not only in Alzheimer's, but shared across other neurodegenerative diseases, including Parkinson's and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis," says Selleck.

"These findings suggest a promising target for future treatments that could rescue the earliest abnormalities that occur."

The research has been published in iScience.