Scientists are investigating whether the psychedelic ingredient in magic mushrooms can put a brain 'back together' after head injuries.

Preliminary research on female rats, which is not yet peer-reviewed, has "absolutely stunned" researchers at Northeastern University with its possibilities.

In a preprint of the paper, the authors explain how psilocybin was able to restore brain function in adult rodents after a series of mild, repetitive head injuries, designed to mimic the sort of damage that typically affects athletes, military personnel, the elderly, and victims of domestic violence.

While the same benefits of psilocybin may not occur in human brains, the results among rodents align with growing clinical research that suggests psilocybin can reduce brain inflammation and change how our brains are wired. Not only does the drug seem to improve brain connections, it may alter the very way our central nervous system processes and shares information.

Initial research on humans suggests psilocybin's effects on the brain may help those with depression when combined with therapy, as well as those with anorexia, substance abuse, and various other mental health disorders.

In some studies on animals, the drug can even 'regrow' lost neural connections.

Scientists are now exploring whether similar benefits can treat a concussion crisis in brain health.

To test this idea, researchers gave what they describe as "bump on head, ice pack" injuries to 16 adult female rats without anesthesia for three days in a row. Half an hour after each of the daily injuries, half the rats received an injection of psilocybin.

"It really did incredible things," says psychologist Craig Ferris from Northeastern University.

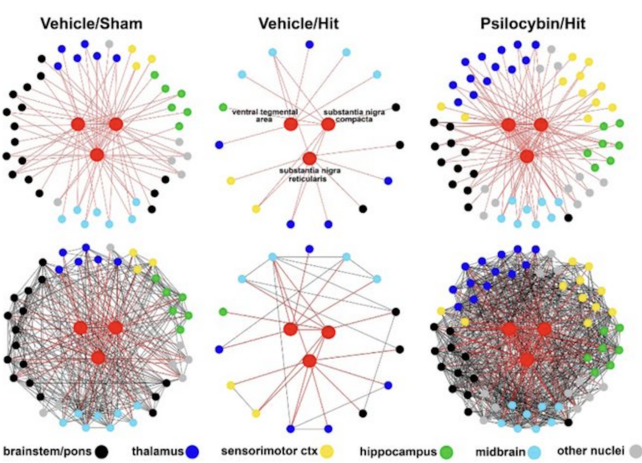

"What we found was that with head injuries… functional connections go down across the brain. You give the psilocybin and not only does it return to normal, but the brain becomes hyper connected."

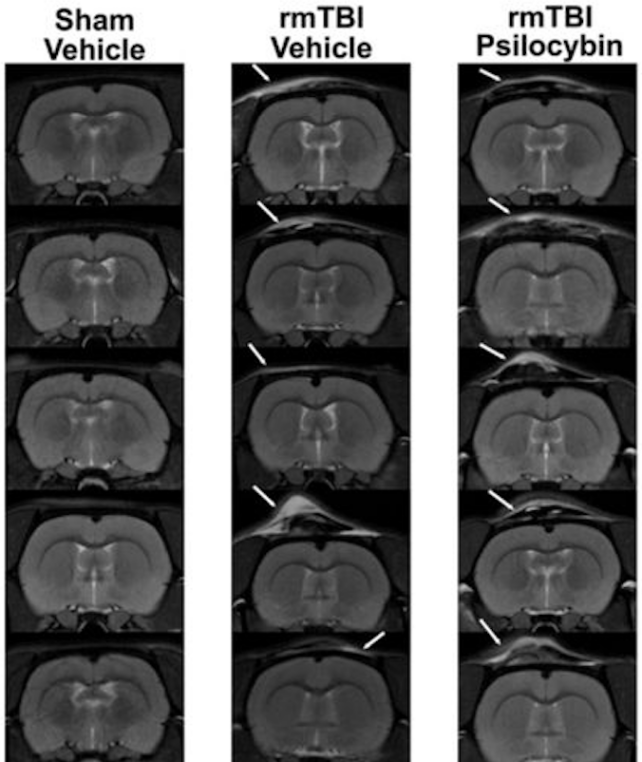

On the third day of the experiment, scientists scanned the brains of all their rats, including eight control subjects that did not receive any knocks to the head. They then scanned the brains again 22 days later, before euthanizing the rats for further tissue analysis.

The team says that the results from that experience look similar to what you'd see in MRI scanners of people after repetitive traumatic brain injury.

Compared to the rats that received head knocks without psilocybin, however, those rats given a small dose of the psychedelic treatment showed reduced swelling in their brains. They still had more than rats given no knocks at all, but the overall harm was significantly alleviated.

This was especially true in brain regions like the hippocampus, somatosensory cortex, prefrontal cortex, thalamus, cerebellum, olfactory system, and basal ganglia.

The authors also noticed the rats treated with psilocybin showed reduced hyper-reactivity to CO2 following their head injuries and "dramatic" differences in their functional connectivity.

The untreated rats with mild head injuries showed few network connections with the thalamus and sensorimotor cortex, whereas connections in the treated rats were "very pronounced" and more similar to rats who had not received any head knocks.

Last but not least, the team found a significant increase in phosphorylated tau, which is a protein linked to dementia, in those rats who had received head knocks without psilocybin.

"The ability of psilocybin to reduce tau phosphorylation suggests potential therapeutic applications beyond repetitive mild traumatic brain injury, possibly extending to other tau-related neurodegenerative disorders," the authors write.

"This translational model successfully bridges bench-to-bedside by replicating clinical observations and identifies psilocybin as a promising therapeutic agent for repetitive mild head injury and its neurodegenerative consequences."

But it's not just the sports bench where this new type of treatment could prove life-changing.

If the symptoms of mild traumatic brain injury persist, they can increase the risk of dementia, Parkinson's disease, and chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE).

Figuring out how to treat brain damage before it causes chronic issues is an ongoing challenge for neuroscientists. Psilocybin could be the ticket to better preventative therapies.

The preprint was published in bioRxiv.