In 1856, an American scientist that history almost forgot, Eunice Foote, discovered the extraordinary ability of a teensy, transparent molecule, carbon dioxide, to absorb heat.

From a simple experiment, she rightly deduced that an atmosphere containing CO2 would "give to our Earth a higher temperature" – describing the driving force of global warming and providing a molecular mechanism to earlier musings about what keeps our planet warm.

Now, more than 160 years later, scientists have realized there's more to the story. The reason why CO2 is so good at trapping heat essentially boils down to the way the three-atom molecule vibrates as it absorbs infrared radiation from the Sun.

"It is remarkable," Harvard University planetary scientist Robin Wordsworth and colleagues write in their new preprint, "that an apparently accidental quantum resonance in an otherwise ordinary three-atom molecule has had such a large impact on our planet's climate over geologic time, and will also help determine its future warming due to human activity."

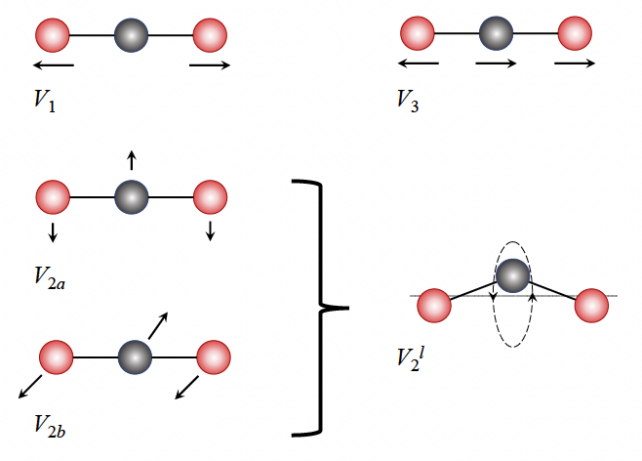

When hit with incoming rays of light at certain wavelengths, CO2 molecules don't just jiggle about as one fixed unit as you might expect. Rather, CO2 molecules – which are made up of one carbon atom flanked by two oxygens – bend and stretch in certain ways.

As you can see in the diagram below, the two oxygen atoms can stretch outward and the central carbon atom may or may not follow, or the carbon atom can swivel around the main axis of the molecule, bending it.

A chance alignment in two of these vibrational patterns creates a type of quantum hum in CO2 molecules called Fermi resonance, which can make the molecules vibrate more.

In turn, this broadens the range of radiation that gets absorbed by CO2, as Wordsworth explained in an interview with New Scientist's Alex Wilkins. "It's this broadening which is really critical to understanding why carbon dioxide is an important greenhouse gas," he said.

You can think of Fermi resonance like a pendulum made up of two weights connected to the same string: as they swing, they work to boost the amplitude of each other's motion.

Other studies have recently estimated that the Fermi resonance of CO2 contributes around half of its total warming effect, otherwise known as radiative forcing.

But starting with the fundamental properties of CO2, Wordsworth and colleagues have described the interactions between the molecule's vibrational states and the extra heat it subsequently traps using a series of equations that blend molecular spectroscopy (the absorption patterns of molecules) and climate physics.

"This outcome provides further evidence, if such evidence were needed, of the rock-solid foundation of the physics of global warming and climate change," Wordsworth and colleagues write in their preprint, which has been posted arXiv ahead of peer review.

Aside from providing a simple explanation of how CO2 heats up Earth, the team says their equations might also help scientists run quick estimates of the warming potential of the different mixes of greenhouse gases detected in the atmospheres of other planets, to understand their foreign climates.

"This might be a particularly useful way of increasing intuition and providing a reality check on the results of complex climate models," the researchers suggest.

However, their calculations don't include any overlap of CO2 with other heat-trapping greenhouse gases such as methane or the radiative effects of clouds, which reflect sunlight as well, so they might need some further tweaking.

As it stands, the team's work instills a new appreciation of teensy, transparent CO2 – the fateful molecule upon which our lives depend.

"One can imagine that with minor differences in the quantum structure of CO2, this resonance might be changed or inhibited, and the past and future evolution of our planet's climate would be very different," the researchers conclude.

The study has been accepted for publication in an upcoming edition of The Planetary Science Journal. Until then, you can read the preprint version at arXiv.org.