A remote, protected world heritage area has been found to be the home of living stromatolites - the world's oldest evidence of lifeforms.

They were found in freshwater spring mounds in the karstic wetlands of a wilderness area in Tasmania, Australia. These are wetlands with peaty soils over carbonate bedrock such as limestone, and waters that dissolve the bedrock into cave systems.

If you're looking for the oldest identifiable fossils on the planet, you're looking for stromatolites. Palaeontologists have found such fossils dating back 3.7 billion years, a time when the first single-celled organisms appeared during the Archaean Eon.

The shape of stromatolites can vary, but they typically appear as rock structures. They are formed by single-celled photosynthesising microbes such as Cyanobacteria, which collectively form a layer called a biofilm.

This biofilm is made of filaments composed of single-celled organisms, a bit like a felted mat. It traps sediment and minerals from the water and cements it in place, building up the stromatolite layer by painstaking layer.

For this reason, stromatolites are an excellent tool for studying Earth's geological history.

There are few places around the world where living stromatolites can be found today. They're usually found in hypersaline waters, because the salt deters animals from grazing. There are a few freshwater colonies too, such as Laguna Bacalar in Mexico and Salda Gölü in southern Turkey.

This new discovery marks the first time living stromatolites have been discovered in Tasmania, in a river catchment that's part of the UNESCO-listed Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area.

"The discovery reveals a unique and unexpected ecosystem in a remote valley in the state's south west," said lead author Bernadette Proemse, a geochemist at the University of Tasmania.

"The ecosystem has developed around spring mounds where mineral-rich groundwater is forced to the surface by geological structures in underlying limestone rocks. The find has proved doubly interesting, because closer examination revealed that these spring mounds were partly built of living stromatolites."

The composition of the bacterial community, the paper said, is unique, consisting of Cyanobacteria, Alphaproteobacteria and an unusually high proportion of Chloroflexi, followed by Armatimonadetes and Planctomycetes.

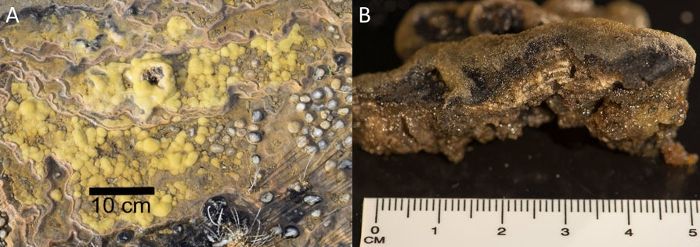

The stromatolites are unusual too, rising several centimetres above the surface of the water, suggesting, the research team noted in the paper, a "terrestrial" variant.

A cross section of the structure reveals alternating light and dark layers each about a millimetre thick. Spectroscopy confirms that they are made of calcium carbonate.

Stromatolites in site (left) and the calcite layers (right). (Proemse et al./Scientific Reports)

Stromatolites in site (left) and the calcite layers (right). (Proemse et al./Scientific Reports)

The waters in which the stromatolites grew are slightly alkaline and dominated by calcium bicarbonate, so this makes sense.

Like hypersaline environments, alkaline waters are also inhospitable to other organisms - and it's possibly this factor that allows the stromatolites to thrive. The spring mounds, the researchers noticed, were littered with the shells of dead freshwater snails.

"This is good for stromatolites because it means there are very few living snails to eat them," Proemse said. "Fortuitously, these Tasmanian 'living fossils' are protected by the World Heritage Area and the sheer remoteness of the spring mounds."

Now further research will be needed to determine whether stromatolites can be found at other sites in the World Heritage Area.

The research has been published in the journal Scientific Reports.