A rare script from a language in Liberia has provided some new insights into how written languages evolve.

"The Vai script of Liberia was created from scratch in about 1834 by eight completely illiterate men who wrote in ink made from crushed berries," says linguistic anthropologist Piers Kelly, now at the University of New England, Australia.

"Because of its isolation, and the way it has continued to develop up until the present day, we thought it might tell us something important about how writing evolves over short spaces of time."

(Kelly et al, Curr. Anthropol., 2022)

(Kelly et al, Curr. Anthropol., 2022)

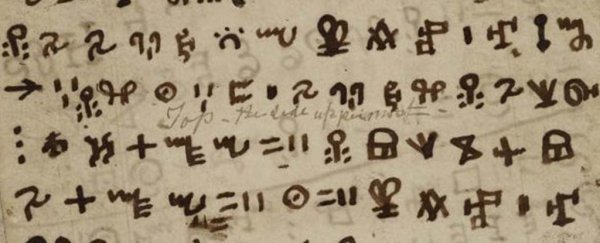

Image: Earliest Vai script dated to 1834 (left) and the same passages written in the modern version of the text (right).

We might all take the written word for granted these days, but researchers still don't know exactly how this early human technology came to develop into the ubiquitous necessity that it is today.

As far as we know so far, the invention of writing occurred around 5,000 years ago in the Middle East and has been reinvented over and over again. New writing systems are still being created today, in places like Nigeria and Senegal.

Even the earliest writing systems are thought to have been formed by small groups of people within a single generation, just like the Vai script. However, as they moved through generations, the team suggests these systems became simpler over time.

"There's a famous hypothesis that letters evolve from pictures to abstract signs," says Kelly.

For example, "the iconic ox's head of Egyptian hieroglyphics transformed into the Phoenician [aleph] and eventually the Roman letter A," the team explains in their paper.

(ScienceAlert; adapted from Wikipedia)

(ScienceAlert; adapted from Wikipedia)

"But there are also plenty of abstract letter-shapes in early writing. We predicted, instead, that signs will start off as relatively complex and then become simpler across new generations of writers and readers," Kelly notes.

The eight Vai creators set out to design symbols for each of their language's syllables, inspired by a dream. Their chosen symbols represented physical things like a pregnant woman, water, and bullets, as well as more abstract traditional emblems.

The transformation of the Vai letters. (Momolu Massaquoi 1911)

The transformation of the Vai letters. (Momolu Massaquoi 1911)

It was then taught informally by a literate teacher passing their knowledge of the script to an apprentice student (with 200 individual letters that must have been a challenge to remember!). This practice is still used today to teach the written language, which is now even used to communicate pandemic health messages.

Kelly and colleagues from the Max Planck Institute analyzed the 200-syllabic alphabet of the Vai people from 1834 onwards using archives across several countries. Below is an animation of what they observed for three of the Vai letters: ꔫ 'bhi' , ꗌ 'tho', and ꔱ 'fi'.

Over the first 171 years of its history, the Vai script did indeed become increasingly compressed. The simplification occurred over generations of users; symbols with the highest complexity were simplified the most.

These changes are far from random, the research team explained. Languages pass a kind of natural selection process via memory and learning, where the hardest to recall features do not survive.

"Visual complexity is helpful if you're creating a new writing system. You generate more clues and greater contrasts between signs, which helps illiterate learners. This complexity later gets in the way of efficient reading and reproduction, so it fades away," says Kelly.

As the letters became less complex, Kelly and team found they also became more uniform. This is despite the language never having been adopted for mass production or for bureaucratic needs. These uses are what seemed to help standardize other languages – for example, Mesopotamia's writing standardization coincided with the implementation of state-wide systems.

Changes in tools, from new writing implements and the invention of paper to use with computers also likely play a role in simplifying languages.

"However the fact that Vai continued to compress over the entire length of the 19th century, at a time when there was little change in writing media, indicates that shifts in writing technology cannot be the full story," the researchers write.

While the rapidness of this writing system's evolution seems rather remarkable, the researchers suggest it occurred because its inventors and users already knew what writing is capable of, because they knew of its use in other cultures. This may have encouraged Vai people to quickly optimize their system.

However, there's a compromise between simplification and ensuring each symbol remains distinctive, which may be why some scripts hold on to complexity. The researchers are hoping to explore this further.

This research was published in Current Anthropology.