For such a lush, verdant paradise, the Amazon rainforest's soil can be surprisingly barren. Yet mysteriously fertile "dark earth" called terra preta can be found in patches across hundreds of sites, the origins of which have sparked debate among scientists.

Now new research from the US and Brazil says ancient Amazonians intentionally enriched areas of the forest to nourish crops for centuries, locking up carbon in the process.

Modern indigenous groups still use these ancient soil secrets, which could inspire agricultural practices and efforts to mitigate climate change.

"Our results demonstrate the intentional creation of dark earth," the authors write, "highlighting how Indigenous knowledge can provide strategies for sustainable rainforest management and carbon sequestration."

Researchers had been working with Indigenous communities in the Amazon since the early 2000s, and those observations and data were analyzed alongside newer data from 2018 and 2019.

Darker soil around archaeological sites in the Kuikuro Indigenous Territory intrigued lead author Morgan Schmidt, a geographer and archaeologist who was then at the University of Florida.

"When I saw this dark earth and how fertile it was, and started digging into what was known about it, I found it was a mysterious thing – no one really knew where it came from," Schmidt says.

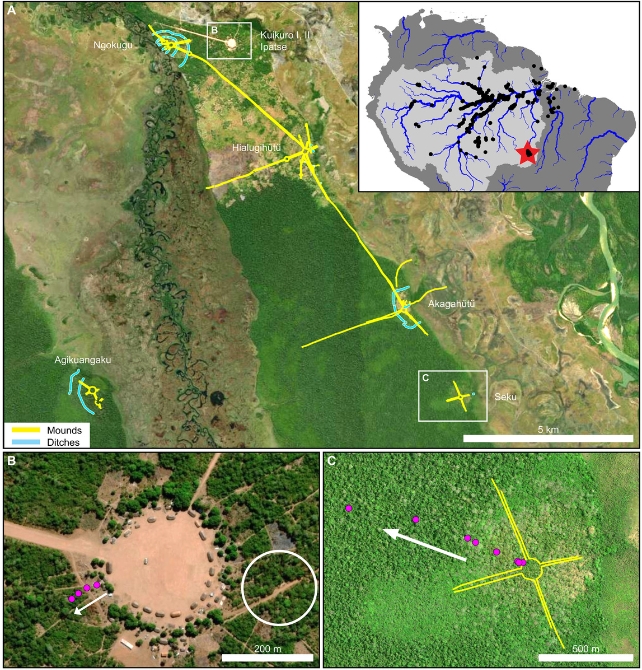

Located in the Upper Xingu River basin in the southeastern Amazon, the Kuikuro Indigenous Territory has modern villages as well as archaeological sites that their ancestors likely inhabited.

"Archaeological research has demonstrated cultural continuity from ancient to modern peoples in the Upper Xingu region," the team writes, "offering an opportunity to examine linkages between present and past activities that have modified soils."

In a modern village, Kuikuro II, the team discovered soil that was strikingly similar to that in the the archaeological sites. Hundreds of people live in Kuikuro II and rely on the fertile soil to grow food like cassava.

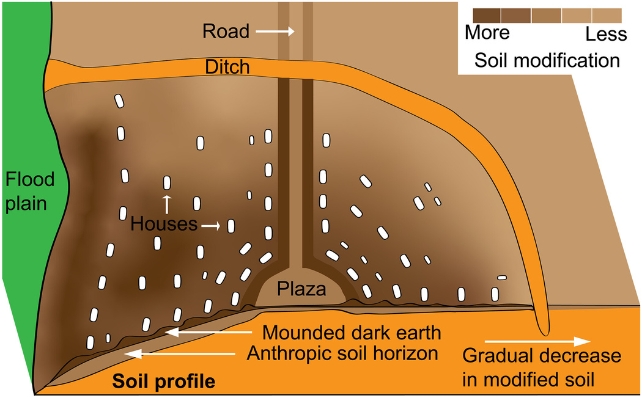

In both the ancient and modern sites, the soil fertility was higher in the residential centers than in the periphery. Throughout the residential areas, 'middens' are created for waste and food scraps. After decomposing, these waste piles mix with barren soil to form dark, fertile soil that villagers plant crops in.

"We saw activities they did to modify the soil and increase the elements, like spreading ash on the ground, or spreading charcoal around the base of the tree, which were obviously intentional actions," Schmidt says.

Kuikuro people were interviewed and co-authored the research paper, and it was clear that they intentionally produce dark earth through modern village practices.

To dig into the past, soil from plazas and roads surrounding ancient villages was compared to terra preta from middens – in residential areas and surrounding the roads and plazas.

Samples from both modern and ancient residential areas had significantly higher levels of organic carbon and lower acidity than those from peripheral areas.

"The key bridge between the modern and ancient times is the soil," says Samuel Goldberg, a data analyst at Massachusetts Institute of Technology at the time. "These practices that we can observe and ask people about today, were also happening in the past."

Some elements, like phosphorus, potassium, and calcium, were more than 10 times as concentrated in the residential samples.

"These are all the elements that are in humans, animals, and plants, and they're the ones that reduce the aluminum toxicity in soil, which is a notorious problem in the Amazon," Schmidt explains.

At one ancient site, Seku, researchers estimated 4,500 tonnes of soil carbon were stored, while the modern Kuikuro II village had 110 tonnes of carbon stored in middens.

"The ancient Amazonians put a lot of carbon in the soil, and a lot of that is still there today. That's exactly what we want for climate change mitigation efforts," Goldberg says.

"Maybe we could adapt some of their indigenous strategies on a larger scale, to lock up carbon in soil, in ways that we now know would stay there for a long time."

The study has been published in Science Advances.