The colorful chaos of a wildflower meadow is a much 'greener' alternative to a perfectly manicured patch of grass, a team of researchers led by the University of Cambridge says.

Cultivating a lawn is a highly popular, centuries-old tradition in much of the Western world. Yet as great as these uniform blankets of green are for, say, playing sports, they do not foster the healthiest natural habitats.

Maintaining a uniform grass garden is costlier, more time-consuming, and worse for the environment than simply letting nature take over.

And when nature has its way, the sight is pretty darn beautiful.

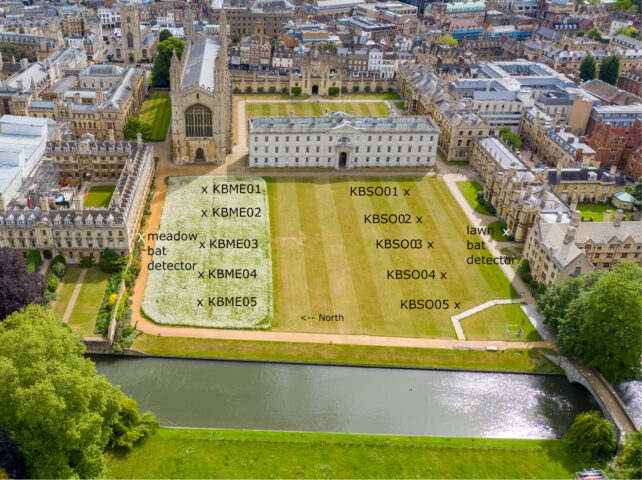

To prove it, a team at King's College has broken a long-held tradition. In 2019, they stopped nearly half of the college's iconic Back Lawn from being mown for the first time since it was laid in 1772 and planted a wildflower meadow mix in the topsoil of this region.

A sprinkling of poppies, cornflowers, and oxeye daisies later burst into life. According to new findings, the football field-sized patch of color now supports more than 3.6 times as many plants, spiders, and bugs as nearby lawns.

In fact, the biomass of invertebrates living in the meadow is 25 times higher than what lives in a regular lawn, including twice as many species in need of conservation.

Researchers say the meadow supported about four times as many declining plant species in 2021 as it once did as a lawn.

With the flowers, the bugs soon followed, and with them came their predators. Local bats now forage in the meadow three times as often, researchers say.

"I was really surprised, actually, at the magnitude of the change for such a small area," marvels plant ecologist Cicely Marshall from the University of Cambridge.

"For species that might look for insects over several miles in a single evening, it's incredible that our small meadow impacted [bat] behavior," she adds.

To start, the meadow was only seeded with 33 species of plant. Already, it hosts at least 51 other species as well.

Even better, no gardener needs to mow, fertilize, water, or spray these plants with pesticides.

Because gardens can store carbon over time, that saves a lot of potential emissions.

Researchers estimate meadows could save about 1.36 tons of carbon emissions per hectare per year, mainly from the loss of mowing and a lack of fertilizing.

That's equivalent to a return flight between London and New York. And this experiment was only conducted on a small patch of land.

Previous studies have also shown that even mini meadows can positively impact wildlife. Imagine if those results were replicated in numerous yards and public spaces.

"Many people mow their lawns because that's what they've always done," says University of Cambridge horticulturalist Steve Coghill.

"There's a perception that a close-mown lawn demonstrates you're caring for the garden more."

But breaking with this tradition could be a more caring act. Coghill says he's not frightened to be contrary for "the right reasons".

"Britain is one of the most deforested countries in Europe. Anything we can do to bring back some biodiversity is worth a go."

The students and staff at Cambridge certainly don't seem to mind. In a survey of a few hundred residents at King's College, researchers found many students preferred a mix of meadows and lawns to lawns only.

Some said they found lawns 'pretentious' or 'sterile and uninviting'. Most found the wildflower meadow more aesthetically pleasing.

"There will always be people who prefer the aesthetic of lawn," says Marshall, "and lawns definitely have a place – they're hard-wearing and good for recreation – you're not going to play football on a meadow!"

But she says that UK's urban lawns are an ample opportunity for biodiversity conservation.

Compared to a lawn, for example, the meadow at Cambridge reflects much more sunlight, which researchers say could help help "maintain a cooler urban microclimate under future global warming."

"People who take the first step can help others to see the benefits. Well-respected, prominent institutions like King's College can act as role models that may influence public opinion."

The study was published in Ecological Solutions and Evidence.