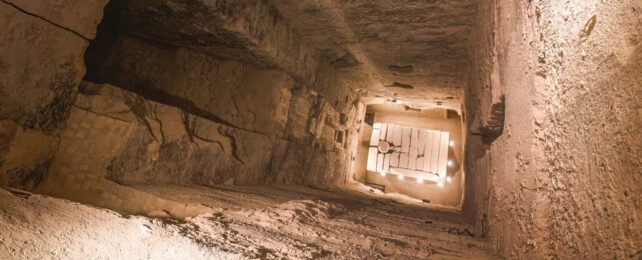

The magnificent step pyramid standing tall in the ancient Egyptian necropolis of Saqqara is truly one of the wonders of the ancient world.

Erected some 4,500 years ago, the tomb of the pharaoh Djoser is the earliest known example of Egypt's colossal stone structures; a monument not just to the king but to the engineering ingenuity of the people who inhabited the land thousands of years ago.

How this architectural marvel was constructed – especially given its sharp departure from any building that came before – has been of intense interest to archaeologists and historians.

Now a team led by Egyptologist Xavier Landreau of Paleotechnic in France may have uncovered a significant clue.

A previously unexplained structure in Saqqara, they argue, is in fact a check dam, supporting the hypothesis a water-powered lift helped move materials used in the pyramid's construction.

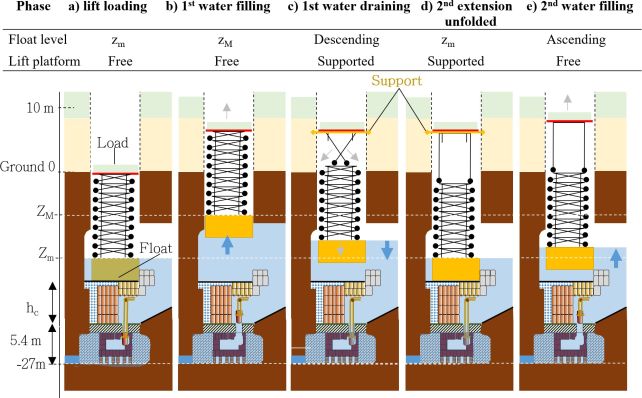

This is bolstered by the discovery of several other features, including what the researchers interpret as the remains of a novel kind of hydraulic lift: a central shaft through which water channelled from below might flow like lava in a volcano, raising a floating platform which would be capable of transporting large rocks to the pyramid's summit.

The novel interpretation of the structure not only helps explain the construction of the pyramid, but several other unidentified features at Saqqara, tying them together in a tidy package.

"Based on a transdisciplinary analysis, this study provides for the first time an explanation of the function and building process of several colossal structures found at the Saqqara site," the researchers write in their paper.

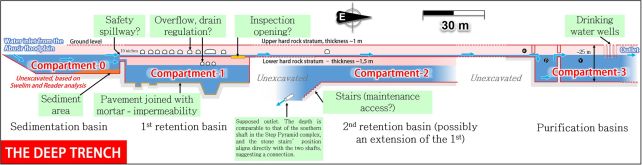

"The results show that the Gisr el-Mudir enclosure has the feature of a check dam intended to trap sediment and water, while the Deep Trench combines the technical requirements of a water treatment facility to remove sediments and turbidity. Together, these two structures form a unified hydraulic system that enhances water purity and regulates flow for practical uses and vital needs. Among the possible uses, our analysis shows that this sediment-free water could be used to build the pyramid by a hydraulic elevator system."

The pyramid of Djoser is deeply impressive; a vast limestone edifice that towers over the surrounding necropolis in the form of six 'steps' that give it a distinctive, iconic profile against the sky.

Its construction marked a turning point for ancient Egyptian civilization, representing the arrival of the giant tombs in which kings and queens were interred for their journey to the afterlife.

Around it, however, there are a few structures whose purpose is less clear.

The Gisr el-Mudir enclosure is a large, rectangular wall enclosing a space that could comfortably hold several football pitches, just a few hundred meters from the pyramid. There are also a series of pits carved into the ground outside the pyramid, in a deep trench that surrounds the pyramid.

The researchers believe these structures may be related. The enclosure, their research finds, could have functioned as a check dam, designed to capture water from the floodplain that once filled the area. Channeling water through trench would have helped filter out sediment as the water passed through each compartment.

Clear water flowing across the dam through a trench and up through the shafts of the pyramid under construction could have been used to raise a wooden platform, elevating heavy materials to where they're needed.

It's a novel suggestion that would need to be supported beyond models suggesting it was possible. We don't know, for example, how much water was available in the area during the time the pyramid was constructed, nor how water flow into and out of the pyramid shafts would have been controlled.

It's also important to note that other means of transport were likely to have been used, in the very least to get heavy materials to the lift or to raise them when water supply was too low for the lift to operate. So the possible use of hydraulic lift technology doesn't negate previous research into how the structure was engineered. Just like today, a mix of technologies suited to a range of needs would have been likely.

What the findings highlight is the possibility that we've underestimated the ingenuity of the ancient Egyptians, and suggest that we need to look more closely at the pyramid construction techniques.

"The hydraulic lift mechanism seems to be revolutionary for building stone structures and finds no parallel in our civilization," the researchers write.

"This technology showcases excellent energy management and efficient logistics, which may have provided significant construction opportunities while reducing the need for human labor. Furthermore, it raises the question of whether the other Old Kingdom pyramids, besides the Step Pyramid, were constructed using similar, potentially upgraded processes, a point deserving further investigation."

The research has been published in PLOS One.