Bits of a fossil discovered jutting out from a Canadian cliff in 2021 could be attached to a rare complete dinosaur skeleton, complete with fossilized skin.

A volunteer field scout, Teri Kaskie, noticed a strange protrusion on a hillside in Dinosaur Provincial Park in Alberta, and University of Reading paleoecologist Brian Pickles, who was leading the search, identified it as a hadrosaur.

"This is a very exciting discovery, and we hope to complete the excavation over the next two field seasons," Pickles says. "Based on the small size of the tail and foot, this is likely to be a juvenile."

Duck-billed hadrosaurs are herbivorous dinosaurs that were common during the late Cretaceous, prospering between 75 and 65 million years ago. This one appears to be only around 4 meters (13 feet) long, whereas adults can reach 10 meters.

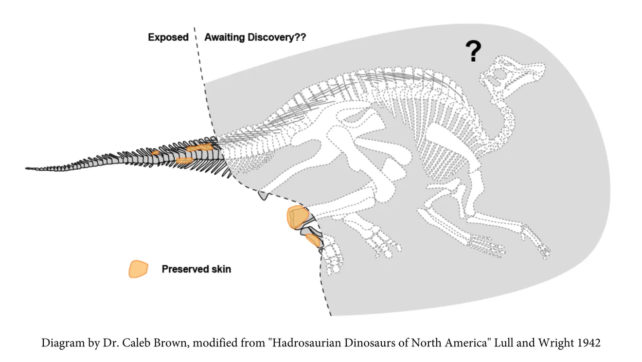

Currently, only its tail and right hind foot are in view, giving researchers a look at its intact fossilized skin. Together, these parts are posed in a way that suggests the dinosaur's entire skeleton lies intact within its ancient encasing.

"Hadrosaur fossils are relatively common in this part of the world, but another thing that makes this find unique is the fact that large areas of the exposed skeleton are covered in fossilized skin," explains paleontologist Caleb Brown from the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Paleontology.

"This suggests that there may be even more preserved skin within the rock, which can give us further insight into what the hadrosaur looked like."

As its skin has been so well preserved, it must have been covered up quickly upon its death around 76 million years ago.

"This animal probably either died and then immediately got covered over by sand and silt in the river," Pickles told USA Today. "Or it was killed because a river bank fell onto it."

"If we're really lucky, then some of the other internal organs might have preserved as well."

It will take months of painstaking work to carve out the block of stone containing the fossil while also protecting the bits already freed from the stone.

The stone will then go to the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Paleontology, where researchers will work to carefully expose the rest of the fossilized remains. This process could take years. With any luck, they will find an intact skull to tell them which species of hadrosaur it is.

"Although adult duck-billed dinosaurs are well represented in the fossil record, younger animals are far less common," says Pickles. "This means the find could help paleontologists to understand how hadrosaurs grew and developed."