A trio of US researchers claim to have successfully tested predictions that it's possible to harvest clean energy from the natural rhythms and processes of our planet, generating electricity as Earth rotates through its own magnetic field.

Though the voltage they produced was tiny, the possibility could give rise to a new way to generate electricity from our planet's dynamics, alongside tidal, solar, wind, and geothermal power production.

In 2016, Princeton astrophysicist Christopher Chyba and JPL planetary scientist Kevin Hand challenged their own proof that such a feat ought to be impossible. The researchers have now uncovered empirical evidence that their proof-breaking idea may actually work, as long as the shape and properties of the conducting material in their method are set to very specific requirements.

"This small demonstration system generates a continuous DC voltage and current of the (low) predicted magnitude," the researchers write in their recent paper.

In the early 20th century, American physicist Samuel Barnett resolved a nagging question over the non-rotation of a magnetic field with respect to its moving electromagnet.

While the proposed difference in velocity between the field and its magnet ought to allow for a voltage to form, proofs such as the one Chyba and Hand spelled out in their 2016 paper showed it wasn't possible. The reason was simple; any electrons pushed by Earth's magnetic field would quickly rearrange themselves and cancel out any difference in charge.

There were some assumptions at work, however, which together with Spectral Sensor Solutions scientist Thomas Chyba, the scientists set out to challenge with a rather specific set of circumstances.

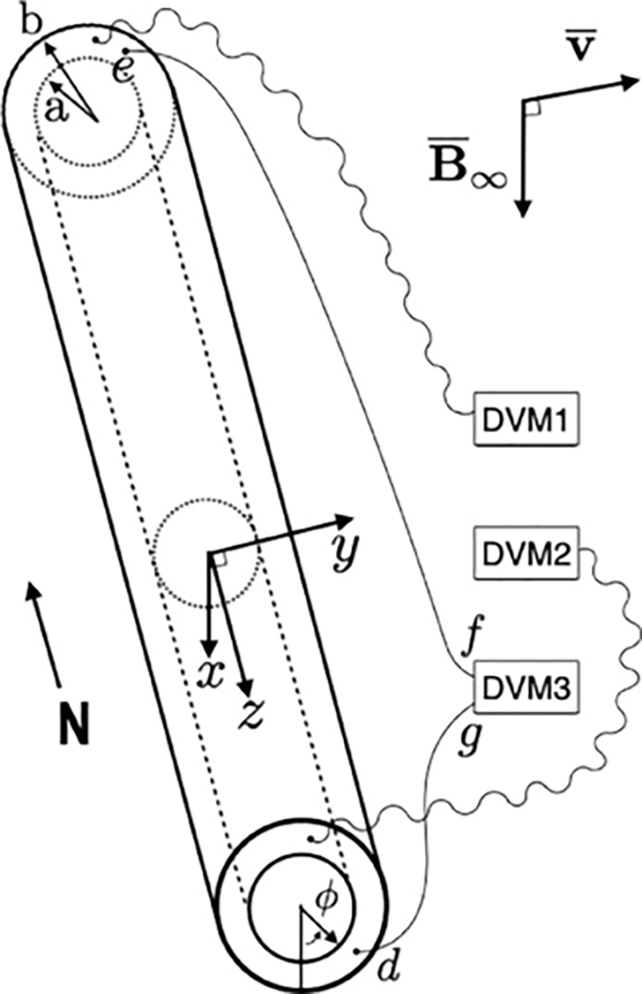

To test them, the team used a 29.9-centimeter (almost one foot) long hollow cylinder made from manganese-zinc ferrite; a material chosen to encourage magnetic diffusion, where magnetic fields are less tightly constrained.

The cylinder was placed in a pitch black, windowless laboratory to minimize photoelectric interference, and angled in such a way as to make it perpendicular to both Earth's rotation and magnetic field.

After all was measured and accounted for, a voltage of 18 microvolts remained. This small potential disappeared when different cylinders were used, or the same cylinder was set at a different angle, suggesting it was being generated by Earth's rotation.

"The device appeared to violate the conclusion that any conductor at rest with respect to Earth's surface cannot generate power from its magnetic field," says Christopher Chyba.

The researchers observed the same response from the material in a second location, this time in a residential building rather than a laboratory.

It's exciting and promising research, but we shouldn't get carried away at this early stage – and indeed the researchers themselves are being cautious. We're talking about a very small amount of electricity here, generated with a very specific experimental setup.

"Both papers [2016 and 2025] talk about how it might be scaled up, but none of that has been demonstrated, and it might well prove not to be possible," says Christopher Chyba.

"And in any case, the first thing that needs to happen is that some independent group needs to reproduce – or rebut – our results, with a system closely similar to our own."

The research has been published in Physical Review Research.