Soft, squishy, ancient spiders are hard to investigate - they don't fossilise as easily as bones or exoskeletons. So you can imagine how excited researchers were to find 10 brand new spider fossils in a relatively unexplored area called the Jinju Formation.

The Jinju Formation is a geological area of South Korea from the Mesozoic era, between 252 and 66 million years ago. This new spate of fossils, which researchers from the Korea Polar Research Institute and the University of Kansas found in shale, has increased the number of known spiders in the Jinju Formation from just one to a whopping 11.

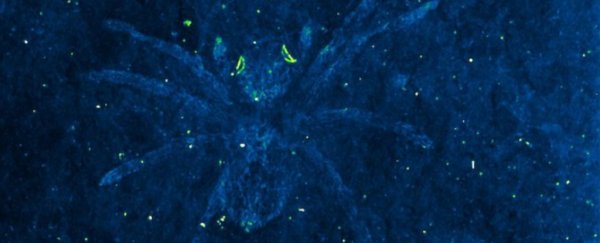

But two of these spider finds were even more exciting than the rest – their eyes still reflected light 110 million years after they died.

"Because these spiders were preserved in strange slivery flecks on dark rock, what was immediately obvious was their rather large eyes brightly marked with crescentic features," said Paul Selden, geologist at The University of Kansas.

"I realised this must have been the tapetum - that's a reflective structure in an inverted eye where light comes in and is reverted back into retina cells."

This structure aids night vision. Human eyes don't have a tapetum, but many animals do; for example, it's what makes cat eyes look so eerily shiny in the dark.

The researchers believe this is the first preservation of a spider eye tapetum in the whole fossil record.

"In spiders, the ones you see with really big eyes are jumping spiders, but their eyes are regular eyes - whereas wolf spiders at nighttime, you see their eyes reflected in light like cats," explained Selden.

"So, night-hunting predators tend to use this different kind of eye. This was the first time a tapetum had been in found in fossil."

"It's nice to have exceptionally well-preserved features of internal anatomy like eye structure. It's really not often you get something like that preserved in a fossil." he added.

Most ancient spiders are discovered in amber because it helps preserve the soft bodies of the arachnids.

However, the researchers think that if these spiders - which have been named Koreamegops samsiki and Jinjumegops dalingwateri - had been found in amber, the tapetum might have been missed.

"They don't have hard shells so they very easily decay," Selden said. "It has to be a very special situation where they were washed into a body of water. Normally, they'd float. But here, they sunk, and that kept them away from decaying bacteria.

"These rocks also are covered in little crustaceans and fish, so there maybe was some catastrophic event like an algal bloom that trapped them in a mucus mat and sunk them - but that's conjecture."

The researchers think that these newly discovered spiders would have been occupying the same niche as the jumping spider does today.

"But these spiders were doing things differently. Their eye structure is different from jumping spiders," Selden explained.

Finding 10 new spiders is a huge win for the diversity of spiders from the Cretaceous period – because of the lack of fossils we just don't know what much about these ancient creepy crawlies.

But with finds like this, that looks set to change.

The research has been published in the Journal of Systematic Palaeontology.