The earlier we can catch the signs of Alzheimer's, the earlier we can do something about it, and new research has spotted a series of biomarkers in the body that can flag up Alzheimer's more than 30 years before the recognisable symptoms appear.

The study sample is small, but the result remains intriguing. Reviewing the records of a group of 290 people, largely made up of individuals at higher risk of Alzheimer's because of family history, scientists were able to track various biological and clinical changes in relation to Alzheimer's in the participants between 1995 and 2013.

At the end of the analysis period, 81 of the participants had developed cognitive problems or dementia, and their records showed a number of differences to the rest – such as subtle changes in test scores measuring thinking processes some 11-15 years earlier.

Looking at cerebrospinal fluid levels, the researchers also found increases in tau protein (previously linked to Alzheimer's). Using computer modelling, they estimated this increase started an average of 34.4 years before Alzheimer's symptoms developed in the patients, which means it could be quite an effective early warning system.

"Our study suggests it may be possible to use brain imaging and spinal fluid analysis to assess risk of Alzheimer's disease at least 10 years or more before the most common symptoms, such as mild cognitive impairment, occur," says one of the researchers, Laurent Younes from the Johns Hopkins University in Maryland.

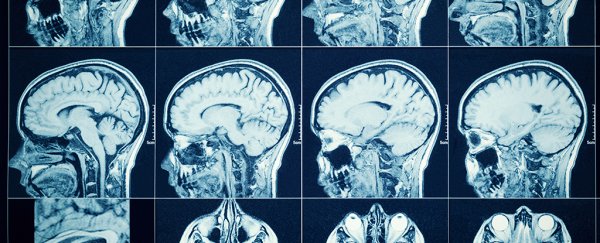

The scientists also had access to MRI scans of the participants, which were crunched through computer algorithms to spot changes in brain anatomy that matched up with patterns of cognitive decline.

The team spotted slight decreases in the rate of change of the size of the medial temporal lobe (linked to memory management) between three and nine years before cognitive impairment became obvious.

And that links into previous work from the same team, using the same computational methods, that found a connection between tissue shrinkage inside the medial temporal lobe and mild cognitive impairment.

All together, this makes for a broad set of biomarkers that could one day be used at different stages of diagnosis – it's not going to be pleasant to be told you might to develop Alzheimer's 30 years ahead of time, but that time gap gives doctors a window to work in.

It should be noted that it's still early days for this research: the group of participants in the study was relatively small, and changes in the brain can differ widely between people, making generalisations difficult.

However, there does seem to be enough of an association here to merit further analysis so we have more tools for developing treatments in the future.

While we can't stop or beat Alzheimer's at the moment, we continue to learn more about it – whether that's more clues about how it starts in the first place, to ways of clearing out tau protein clumps from the brain.

"Several biochemical and anatomic measures can be seen changing up to a decade or more before the onset of clinical symptoms," says one of the team, Michael Miller from the John Hopkins University.

"The goal is to find the right combination of markers that indicate increased risk for cognitive impairment, and to use that tool to guide eventual interventions to help stave it off."

The research has been published in Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience.