Editor's note (24 Jun 2019): Since publication, a report by Quartz has pointed out a potential conflict of interest that wasn't flagged in the paper: Shahar is the creator of an online store for posture-correcting pillows. Additionally, Nature Research, the publisher of the journal Scientific Reports, is looking into alleged issues with the methods used in this study.

Editor's note (19 Sep 2019): The authors have issued an official correction to the paper, withdrawing their bold, yet unsubstantiated claims about hand-held technology being "primarily responsible" for the growths.

Original: The more we learn, the more it seems like our skeletal system is adapting to the unique stresses of modern life. For example, researchers in Australia have found evidence that young people appear to be increasingly growing bony protrusions at the base of their skulls, right above the neck.

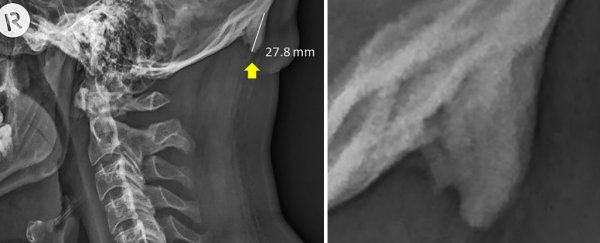

Examining 1,200 X-ray images of adult Australians, the researchers found that 41 percent of those between 18 and 30 had developed these bone spurs, which is 8 percent more than the overall average.

Some were only 10 millimetres long (0.4 inches) and barely noticeable, while others were up to 30 mm in length (1.1 inches), as the scientists described in their 2018 study.

"I have been a clinician for 20 years, and only in the last decade, increasingly I have been discovering that my patients have this growth on the skull," lead author David Shahar, a health scientist at the University of The Sunshine Coast, recently told the BBC.

(Shahar & Sayer, Scientific Reports, 2018)

(Shahar & Sayer, Scientific Reports, 2018)

The growths are happening at a very particular spot of the skull: right at the lower back part of our heads we have a large plate known as the occipital bone, and towards its middle is a slight bump called the external occipital protuberance (EOP), where some of the neck ligaments and muscles are attached.

Because it's an attachment site, the location of the EOP is technically an enthesis. These places in our skeletons can be prone to the development of spiky bone growths called enthesophytes, typically in response to mechanical stress - for example, additional muscle strain.

As Shahar and his colleague Mark Sayers's data indicate, there's a prevalence of EOPs growing longer in young people.

While their sample size is small, the authors have thrown up a bold hypothesis: these bones have become more noticeable since the dawn of the "hand held technological revolution" and the sustained poor posture that our devices bring.

Usually, such 'degenerative' features in a person's skeleton are symptoms of ageing, but in this case, the enlarged EOP was linked to youth, a person's sex, and the degree of forward head protraction.

Being male, for instance, increased an individual's chances of having an extended EOP by more than five-fold; this does align with historical findings of more spiny EOPs in males, and could be explained by increased mass of the head and neck, along with increased muscle power.

And, while the average forward head protraction recorded in this study was 26 mm, the authors say that is significantly larger than what was recorded in 1996.

"We acknowledge factors such as genetic predisposition and inflammation influence enthesophyte growth," the authors write.

"However, we hypothesise that the use of modern technologies and hand-held devices, may be primarily responsible for these postures and subsequent development of adaptive robust cranial features in our sample."

While the findings are fascinating, we must remember that drawing causal links is outside the scope of this study. In fact, the methodology of this research has even been called into question.

But we do acknowledge these ideas do not exist in a vacuum and are supported by extensive research on how mobile devices can alter our musculoskeletal system.

Among users of hand-held devices, for instance, a recent systematic review found that neck-related conditions are up to 67 percent more common today than any other region of the spine.

Other studies have noted that 68 percent of staff and students report neck pain after using mobile devices for, on average, 4.65 hours a day. Bad posture, of course, is nothing new, but this is significantly more time than we humans used to spend craning over a book or writing in our diaries just a few decades ago.

To be clear, these elongated EOPs are not necessarily harmful in their own right, but they could be a symptom of a larger problem. The ways in which our bodies compensate for poor posture could put added stress on certain joints and muscles, increasing our chances for injury or musculoskeletal issues in the future.

"Although the "tablet revolution" is fully and effectively entrenched in our daily activities, we must be reminded that these devices are only a decade old and it may be that related symptomatic disorders are only now emerging," the authors conclude.

"Our results suggest that the younger age group in our study have experienced postural loads that are atypical throughout the other tested age groups."

The research has been published in Scientific Reports.