Though the quest to find water on distant planets is the most talked-about way that researchers are looking for extraterrestrial life, one of our best bets at understanding life's complexities lies with comets, not planets.

In fact, the icy space balls are already known to form amino acids and nucleobases, two key substances needed for life to take root. And now, researchers may have found another necessary ingredient: ribose, the 'R' in RNA.

Before we dive into the new discovery, it's important to understand what life, as we know it, needs to get started, and how we think it may have happened here on Earth. Life on Earth requires three macromolecules: RNA, DNA and proteins. The current understanding is that RNA, or ribonucleic acid, came before DNA on Earth.

However, the conditions needed for ribose, a simple sugar needed for RNA, were not formed yet on Earth before life started. So, the question remained: where did ribose come from?

To answer this, the team of researchers led by chemist Cornelia Meinert from the University Nice Sophia Antipolis in France, set out to recreate the conditions of our early Solar System to see whether or not ribose could form, Deborah Netburn reports for the Los Angeles Times.

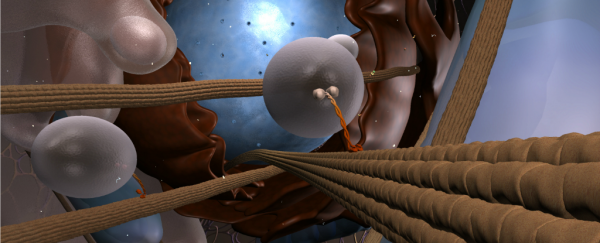

This process involved freezing water, ammonia, and methanol to -195 degrees Celsius, which basically created a fake comet in the lab. Then, when temperatures were right, they blasted it with ultraviolet light so that the 'comet' would experience the same type of radiation that a young star would produce. The last step was to let the comet warm back up and see what molecules were created.

The team discovered about 55 organic molecules were present after analysis, with the most important and exciting being ribose. Though this same experiment had been done countless times across the globe in the past, this team is the first to use multidimensional gas chromatography, a new technique that makes detecting individual molecules easier.

"Our ice simulation is a very general process that can occur in molecular clouds as well as in protoplanetary disks. It shows that the molecular building blocks of the potentially first genetic material are abundant in interstellar environments," Meinert explains.

The discovery hints that ribose from comets or dust clouds might have fallen onto a young Earth, establishing a needed building block for life.

But there are still a few things for researchers to figure out. For example, this study was done in a lab, which means we will need to back up the findings by discovering ribose on a real comet or in a real dust cloud. Also, the team also doesn't know when the ribose actually formed. Was it the heating or the cooling that did the trick?

With any luck, researchers will have these answers in the coming years, with many more missions focusing on comets coming in the near future. Despite its shortcomings, the discovery is a big step in understanding how life on Earth - and possibly elsewhere in the Universe - formed.

The team's study was published in Science.