Researchers have discovered how certain molecules in the body can cause autoimmune diseases, showing the first mechanistic evidence for why they actually occur.

Autoimmune diseases are a problem for over 50 million Americans, and although we are starting to understand more about how to ease symptoms, we still don't fully understand the basics.

"We have known that in autoimmune diseases there are T cells that make us susceptible to disease and T cells that protect us from disease," says one of the researchers, Richard Kitching, from Monash University in Australia.

"Now we know how this happens; it opens the field for new and more targeted treatments to specific diseases."

The new research has found an important interaction between two genes, which helps T cells communicate the correct defensive signals to prevent them attacking the body.

But let's back up a bit, because exactly is an autoimmune disorder?

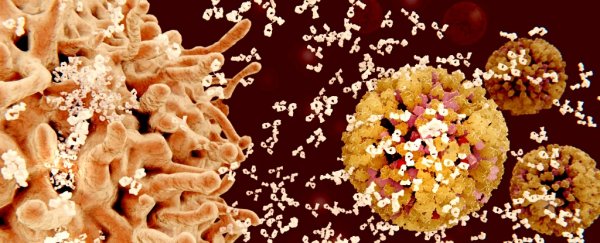

Usually, our immune system is very adept at attacking 'foreign' invaders such as viruses, bacteria, or other micro-organisms that shouldn't be there. But in autoimmune disorders, the immune system begins treating a part of your body as 'foreign' too.

In type 1 diabetes it's destroying the cells that produce insulin, and in rheumatoid arthritis the immune cells attack joints.

Researchers investigated Goodpasture syndrome in mice models, a rare condition caused by the immune system attacking the basement membrane in lungs and kidneys.

Past studies have shown that there are particular proteins, or molecules, in the body that makes you more or less likely, depending on the molecule, to get autoimmune diseases.

The Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA) system is a series of genes that code for the proteins that help the immune system. Some HLA molecules are on the surface of T cells, and will show off tiny bits of invaders to other immune cells to help them destroy it.

"Certain immune molecules, called HLA molecules, are associated with an increased genetic risk to cause autoimmunity, whereas other HLA molecules can protect from disease," says senior researcher, Jamie Rossjohn from Monash University.

For example, some versions (or alleles) of a HLA molecule called DR15 have been shown to increase disease risk of Goodpasture syndrome, multiple sclerosis, and other autoimmune conditions.

Another molecule, called HLA-DR1, has also been linked to a number of autoimmune conditions.

What the researchers didn't know until now is what the mechanism of these molecules actually was, and why it was causing an increase in autoimmune diseases.

The researchers took mice that had been bred to express the human DR15 gene, or the human DR1 gene, and discovered that the DR15 mice began to develop Goodpasture syndrome, but those with just DR1 or both molecules didn't.

"In Goodpasture's disease, when the molecule DR15 is present, it can select and instruct T cells to attack the body. If alone in our body these damaging cells can attack the body's tissues, resulting in very ill patients," says Kitching.

"But when people also have the protective DR1 molecule present these T cells are held at bay and can be overturned."

Although there's a lot more research to do before we can actually look at increasing DR1 molecules in humans, it's an important step forward in understanding how and why our immune system starts seeing the body as a threat.

Even more exciting, is that the researchers are hopeful that these early results will lead to tangible outcomes for patients.

"These particular protective immune cells are specific and are extremely powerful," Kitching says.

"So, if we can encourage them to develop in the body, or expand people's cells outside the body and inject them back into those with disease, this could result in better and more targeted treatments for autoimmune diseases."

The research has been published in Nature.