Scientists have uncovered a relatively large amount of comet dust preserved in Antarctica. Comet dust represents the oldest astronomical particles we have access to, and up until now it was believed that the material couldn't survive on Earth's surface.

"It's very exciting for those of us who study these kinds of extraterrestrial materials, because it opens up a whole new way to get access to them," Larry Nittler, a planetary scientist at the Carnegie Institution for Science in Washington DC, who wasn't involved with the research, told Ilima Loomis from Science. "They've found a new source for something that's very interesting and very rare."

Comest dust is extraordinary because it can give us clues about the materials that helped form the Solar System, but until now it's been pretty difficult to access. Scientists currently need to fly research planes high up into the stratosphere in order to collect tiny amounts of the dust - usually several hours of flying time will only result in one particle being collected.

This small sample size means that scientists haven't been able to do as much research on the dust as they'd like to. But now a relatively huge amount - more than 40 comet dust particles - has been found right here on Earth's surface.

"Two to four more orders of magnitude mass of material is potentially collectible this way," John Bradley, an astromaterials scientists at the University of Hawaii, who worked on the discovery, told Science. "I think it could precipitate a paradigm shift in the way these kinds of materials are collected."

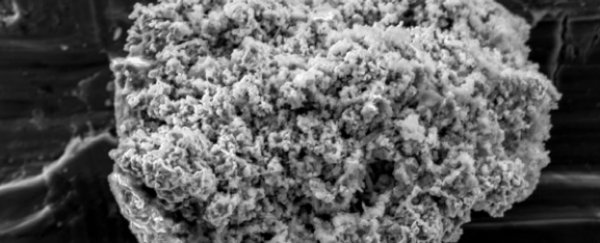

Comet dust, also known as "chondritic porous interplanetary dust particles", is highly porous and extremely fragile, and prior to this discovery scientists thought the particles couldn't survive here on Earth. Back in 2010, French scientists reported that they'd found evidence of dense, unusually carbon-rich comet particles in the Antarctic snow, but it's only now that researchers have been able to confirm that the discovery of comet dust itself.

The researchers found the dust in snow and ice collected from two different Antarctic sites. After melting the ice, they filtered out more than 3,000 micormeteorites - tiny space particles that were 10 microns in diameter or larger. Over five years they analysed these micrometeorites individually under the microscope to work out which could be classified as comet dust.

In the end they found more than 40 particles with the characteristics of comet dust - these particles were indistinguishable from the comet dust collected in the stratosphere, and also matched samples collected from the coma that surrounds a comet by NASA's Stardust mission in 2006.

Publishing their discovery in Earth and Planetary Science Letters, the researchers also report that the comet dust they've found in Antarctica is cleaner than the dust they collect from the stratosphere. This is because in order to capture the dust at the moment, they use plates coated with silicon oil - sort of in the same way you use flypaper to trap flies. Not only is this not super effective, it also means that the few comet dust particles they collect end up contaminated with oil and the organic compounds used to later clean them. So it's hard to scientists to narrow down exactly what organic materials the dust actually contains.

Now the scientists will compare their Antarctic comet particles with the ones collected using planes, and work our which organic materials are contaminants and which are naturally occuring. This will provide some insight into the material that led to the birth of our Solar System.

"The study of these cometary particles will help shed more light on the material that served for planetary formation," meteorite researcher Cécile Engrand from Paris-Sud University in Orsay, co-author of the 2010 French research, told Loomis over at Science. "They are the best witnesses that we have of that period of time."

But importantly, this discovery also suggests that there could be even more sources of comet dust right here on Earth - something we previously thought was impossible.

"Our result shows that such fragile particles can be preserved not only in … snow, but also in ice," said the study's lead author, Takaaki Noguchi, a meteorite researcher at Kyushu University in Fukuoka, Japan.

Source: Science