Being able to erase bad memories and traumatic flashbacks could help in the treatment of a host of different mental health issues, and scientists have found a promising new approach to do just this: weakening negative memories by reactivating positive ones.

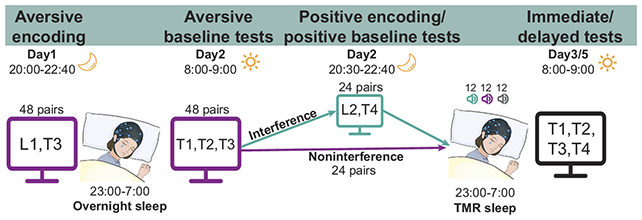

In an experiment covering several days, an international team of researchers asked 37 participants to associate random words with negative images, before attempting to reprogram half of those associations and 'interfere' with the bad memories.

"We found that this procedure weakened the recall of aversive memories and also increased involuntary intrusions of positive memories," write the researchers in their published paper.

For the study, the team used recognized databases of images classified as negative or positive – think human injuries or dangerous animals, compared with calm landscapes and smiling children.

On the first evening, memory training exercises were used to get the volunteers to link negative images with nonsense words made up for the study. The next day, after a sleep to consolidate those memories, the researchers tried to associate half of the words with positive images in the minds of the participants.

During the second night of sleep, recordings of the nonsense words being spoken were played, during the non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep phase known to be important for memory storage. Brain activity was monitored using electroencephalography.

Theta-band activity in the brain, linked to emotional memory processing, was seen to spike in response to the audio memory cues, and was significantly higher when positive cues were used.

Through questionnaires the next day and several days after, the researchers found that the volunteers were less able to recall the negative memories that had been scrambled with positive ones. Positive memories were more likely to pop into their heads than negative ones for these words, and were viewed with a more positive emotional bias.

"A noninvasive sleep intervention can thus modify aversive recollection and affective responses," write the researchers. "Overall, our findings may offer new insights relevant for the treatment of pathological or trauma-related remembering."

It's still early days for this research, and it's worth remembering that this was a tightly controlled lab experiment: that's good in terms of trusting the accuracy of the results, but it doesn't exactly reflect real-world thinking and positive or negative memory formation.

For example, the team says that seeing aversive images in a lab experiment wouldn't have the same scale of impact on memory formation as experiencing a traumatic event. The real thing might be harder to overwrite.

We know that the brain saves memories by briefly replaying them during sleep, and many studies have already looked at how this process could be controlled to reinforce good memories or wipe out bad ones.

With so many variables in play – in terms of types of memories, brain areas, and sleep phases – it's going to take some time to figure out exactly how memory editing could happen, and how long-lasting the effects could be. Nevertheless, this process of overwriting negative memories with positive ones seems to have some promise.

"Our findings open broad avenues for seeking to weaken aversive or traumatic memories," write the researchers.

The research has been published in PNAS.