Over the past decade, scientists have made huge progress in finding ways to see visible light through opaque materials, and now researchers in the US have found a way to see through a mouse's ear in real time.

While we've been looking at objects inside the body using X-rays and ultrasound for several decades, the results are still pretty fuzzy and we often need to perform biopsies to really find out what's going on at a deeper level.

But if we could shine visible light through the body, it would give us far clearer images than any other technique, and would mean we could do away with many intrusive surgeries. We could potentially even use laser light to treat inoperable tumours or brain aneurysms.

"Optical wavelengths interact strongly with organic molecules, so the reflected light is packed with information about biochemical changes, cellular anomalies and glucose and oxygen levels in the blood, writes Zeeya Merali for Nature.

The medical applications are obviously pretty huge, but unfortunately being able to see visible light through an opaque material is tough, because all of this interacting also means that the visible light will be absorbed or scattered by the material. And the light that's absorbed is gone.

But over the past eight years, scientists have started using astronomical techniques in the hopes of salvaging that scattered light. And while we're far off practical applications, there have been some very promising results.

Put very simplistically, the research is based on 'un-scattering' light. When astronomers look at the light from distant planets or stars, they know it's been distorted by the atmosphere. To counteract this, they've created algorithms that reverse the scattering so that they can see the objects clearly. More recently, researchers have started using similar techniques to try to reverse the scattering caused by opaque materials.

Now a team from Washington University in St. Louis in the US has managed to visualise an ink-stained piece of gelatin pressed between the ear of an anaesthetised mouse and a ground-glass diffuser, using visible light.

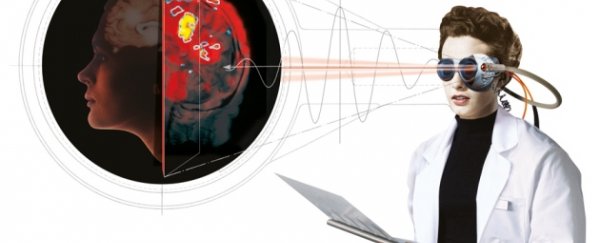

To do this, they used a beam of ultrasound, which isn't easily scattered like visible light is, and focussed it on a single point in the material. They knew that any optical light passing through this focussed point would shift its frequency slightly as a result of the ultrasound beam. They then set up a time-reversing mirror on the other side of the material, so that it would send back this frequency shifted visible light along the path it came in, visualising the target object on its way back. You can see a visual explanation of this in the graphic below, produced by the team over at Nature.

This is a technique that's been used for years, but in the past the light was passed back too slowly for it to be much use for living tissue. "Everything is in motion and we only have a millisecond-scale window to make an image," lead author Lihong Wang explained to Merali.

But Wang and his team managed to speed it up. In their experiment, the visible light image was beamed back to the camera extremely quickly, in just 5.6 milliseconds, which "is fast enough for selected in vivo imagine", he told Merali.

Their research, which was published in Nature, is a huge step towards being able to see what's going on beneath our skin. Although Wang does add that: "moving from a mouse ear, which is relatively thin, to imaging human skin and flesh will still take a lot of extra work".

Still, as Merali explains, this type of imaging has moved forward extremely quickly since 2007, when a team from the University of Twente in the Netherlands was first able to shine a beam of light through a 'solid wall' of glass covered with white paint, and focus it on the other side. Their results were published in 2008.

"Just 10 years ago, we couldn't imagine high-resolution imaging down to even 1 centimetre in the body with optical light, but now that has now become a reality," Wang told Merali. "Call me crazy, but I believe that we will eventually be doing whole-body imaging with optical light."

Aside from the medical benefits, this type of imaging technique also has some pretty important military applications, and could allow soldiers to carry an opaque shield that renders them invisible to their attackers, but that they can see through. "It's not the same as being invisible, but it would allow you to see others while not being seen," Mathias Fink, a physicist who, back in 1990, first pioneered the time-reversal technique that Wang and his team used, told Merali.

But Sylvain Gigan, a French physicist who also works in the field, added that all the researchers in this field are making sure to keep the applications clean. "When we tell people what we do, someone always asks if we'll create a phone app to let people look through shower curtains," he explained in the Nature article. "This is something that could be done with our technique - but we don't intend to do it."

Yeah seriously, don't make it weird, scientists.

Source: Nature