The bones of nomads who lived in what is now southeast Europe thousands of years ago have just yielded humanity's earliest evidence of equestrianism.

According to an analysis of wear on the bones of individuals of the Yamnaya culture that lived across the Eurasian steppe between 3021 to 2501 BCE, these people didn't just keep horses for their milk but rode them to get around and help herd cattle and sheep.

This is an important piece in the puzzle of human development, as the introduction of horse riding dramatically changed the speed and distance with which we could move through the world.

"Horseback-riding seems to have evolved not long after the presumed domestication of horses in the western Eurasian steppes during the fourth millennium BCE," explains archaeologist Volker Heyd of the University of Helsinki in Finland. "It was already rather common in members of the Yamnaya culture between 3000 and 2500 BCE."

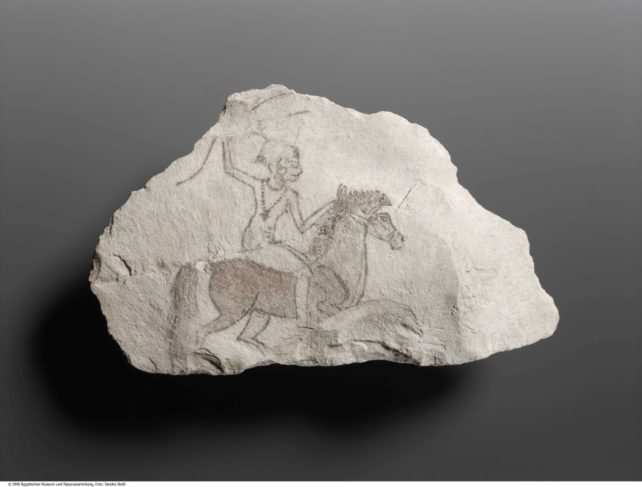

Finding evidence of horse riding in ancient cultures can be a little more difficult than you might think. Some, like the Ancient Greeks and Egyptians, left art depicting riders on horseback; in earlier cultures, whose art perhaps did not last through the ages, evidence of horses, such as their bones in human settlements, is not quite enough to draw conclusions.

Previous studies had found, for example, traces of horse milk on pottery shards, and horse milk peptides in the calculus buildup on teeth of Yamnayan individuals, so it's possible that food was the sole reason for keeping horses.

However, the absence of riding equipment can't be taken as proof that people didn't ride horses, either, since it's possible to ride without them.

But the Yamnaya culture is named after one thing it is very well known for: The pits, known as kurgans, in which their dead were interred. "Yamnaya" is the Russian word for "pit".

In these kurgans, we've found many skeletons in a good state of preservation. The Yamnaya's practices in death have allowed archaeologists and anthropologists to learn more about how they lived.

This is how a team of scientists led by bioanthropologist Martin Trautmann of the University of Helsinki sought to investigate evidence of horsemanship in the Yamnaya. But first, they had to figure out what that evidence might look like.

"Diagnosing activity patterns in human skeletons is not unambiguous," Trautmann explains. "There are no singular traits that indicate a certain occupation or behavior. Only in their combination, as a syndrome, symptoms provide reliable insights to understand habitual activities of the past."

The researchers developed a six set of criteria that, taken together, could be seen as evidence of riding horses. These included stress patterns on the muscle attachment sites on the pelvis and femur; specific changes in the shape of the hip sockets; marks caused by the pressure of the hip socket on the head of the femur; the shape and diameter of the shaft of the femur; wear on the vertebrae caused by repeated shock compression; and any trauma associated with falling from, or being kicked or bitten by a horse.

They made a careful study of 217 skeletons from 39 sites. Of these skeletons, 150 had been archaeologically assigned to the Yanmaya culture. Of the Yanmaya skeletons, 24 were found to possibly have ridden horses.

Five Yanmaya individuals were found to be highly probable riders; another two skeletons that predated Yanmayans, and two more that came after, were also highly probable riders.

One of those two early burials was extremely interesting, the researchers said, suggesting that the team's methodology could have broader applications.

"A grave dated about 4300 BCE at Csongrad-Kettőshalom in Hungary, long suspected from its pose and artifacts to have been an immigrant from the steppes, surprisingly showed four of the six riding pathologies, possibly indicating riding a millennium earlier than Yamnaya," says anthropologist David Anthony of Hartwick College.

"An isolated case cannot support a firm conclusion, but in Neolithic cemeteries of this era in the steppes, horse remains were occasionally placed in human graves with those of cattle and sheep, and stone maces were carved into the shape of horse heads. Clearly, we need to apply this method to even older collections."

The research has been published in Science Advances.