Researchers have identified a brand new 'micro-organ' inside the immune system of mice and humans – the first discovery of its kind for decades – and it could put scientists on the path to developing more effective vaccines in the future.

Vaccines are based on centuries of research showing that once the body has encountered a specific type of infection, it's better able to defend against it next time. And this new research suggests this new micro-organ could be key to how our body 'remembers' immunity.

The researchers from the Garvan Institute of Medical Research in Australia spotted thin, flat structures on top of the immune system's lymph nodes in mice, which they've dubbed "subcapsular proliferative foci" (or SPFs for short).

These SPFs appear to work like biological headquarters for planning a counter-attack to infection.

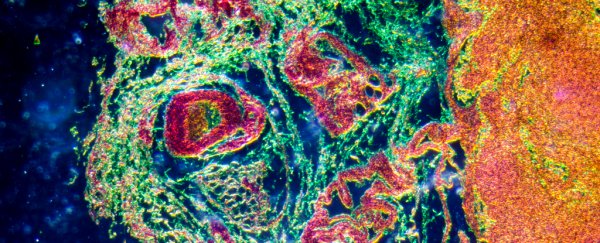

Immune cells gathering at the SPF, with the purple band showing the SPF surface. (Imogen Moran/Tri Phan)

Immune cells gathering at the SPF, with the purple band showing the SPF surface. (Imogen Moran/Tri Phan)

These SPFs only appear when the mice immune systems are fighting off infections that have been encountered before.

What's more, the researchers detected SPFs in human lymph nodes too, suggesting our bodies react in the same way.

"When you're fighting bacteria that can double in number every 20 to 30 minutes, every moment matters," says senior researcher Tri Phan. "To put it bluntly, if your immune system takes too long to assemble the tools to fight the infection, you die."

"This is why vaccines are so important. Vaccination trains the immune system, so that it can make antibodies very rapidly when an infection reappears. Until now we didn't know how and where this happened."

Traditional microscopy approaches analyse thin 2D slices of tissue, and the researchers think that's why SPFs haven't been spotted before – they themselves are very thin, and they only appear temporarily.

In this case the team made the equivalent of a 3D movie of the immune system in action, which revealed the collection of many different types of immune cell in these SPFs. The researchers describe them as a "one-stop shop" for fighting off remembered infections, and fighting them quickly.

Crucially, the collection of immune cells spotted by the researchers included Memory B type cells – cells which tell the immune system how to fight off a particular infection. Memory B cells then turn into plasma cells to produce antibodies and do the actual work of tackling the threat.

"It was exciting to see the memory B cells being activated and clustering in this new structure that had never been seen before," says one of the team, Imogen Moran.

"We could see them moving around, interacting with all these other immune cells and turning into plasma cells before our eyes."

According to the researchers, the positioning of the SPF structures on top of lymph nodes makes them perfectly positioned for fighting off infections – and fast.

They're strategically placed at points where bacteria would invade, and contain all the ingredients required to keep the infection at bay.

Now we know how the body does it, we might be able to improve vaccine techniques – vaccines currently focus on making memory B cells, but this study suggests the process could be made more efficient by also looking at how they transform into plasma cells through the inner workings of an SPF.

"So this is a structure that's been there all along, but no one's actually seen it yet, because they haven't had the right tools," says Phan.

"It's a remarkable reminder that there are still mysteries hidden within the body – even though we scientists have been looking at the body's tissues through the microscope for over 300 years."

The research has been published in Nature Communications.