Famous physicist Albert Einstein, assassinated Japanese prime-minister Hisashi Hamaguchi, and English engineer Charles Babbage all have at least one thing in common; pickled brains – all cut out of their skulls and preserved after their deaths so researchers could study their genius.

The brain of 17th century French philosopher René Descartes is now dust, but it hasn't stopped researchers from scanning the inside of his skull to learn more about his grey matter - which it turns out is remarkably normal, except for a slight bulge at the front.

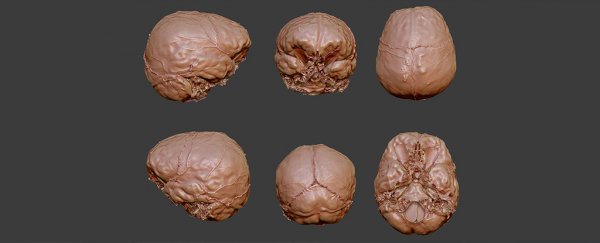

Research carried out by a team of French and Dutch scientists involved creating a virtual endocast based on a CT-scan of Descartes' brain case, which allowed them to study the size, shape, and surface of the philosopher's brain compared with 102 physical casts from a diversity of other specimens.

If you're not well acquainted with Monsieur Descartes, you might be familiar with his famous quote, "I think, therefore I am", a reference to the fact we can doubt many things except our own mind's existence.

You can also thank him for marrying Euclidean geometry with algebra to form the Cartesian plane – commonly used when you drew graphs at school.

Descartes' revolutionary contributions to philosophy and mathematics suggest his mind was somewhat remarkable, but whether extraordinary minds reflect extraordinary lumps of brain meat has been a topic of interest for anatomists for centuries.

The philosopher himself would have found it interesting, no doubt, being one of the first to question how the physics of the brain and the qualities of the mind operated (for those interested, he argued the mind wasn't itself a physical thing, but connected with the brain in the pineal gland).

When Einstein passed away in 1955, a pathologist named Thomas Harvey controversially kidnapped his brain, preserved it, took a few snapshots, measured it, cut it up into 240 pieces and parcelled them out to anybody interested in analysing it further.

Studies have suggested the genius physicist might have had a larger corpus callosum connecting his hemispheres, larger ratio of 'helper' glial cells to neurons, and an unusual size and pattern of grooves on his parietal lobes.

Putting the ethics of Harvey's actions aside for one moment, the relevance of such variations discovered in Einstein's neural anatomy and cytology has inspired debate ever since.

The researchers in this latest study concluded that – for the most part – Renee Descartes had a rather mundane brain.

"The different dimensions quantified on the endocast of René Descartes are within the range of variation observed in our sample of extant modern humans," the researchers wrote.

The cast's total volume was 1540 cubic centimetres (94 cubic inches), which is in the ballpark of the average modern male brain.

One area did happen to stand out slightly, however.

The frontal cortex seemed to bulge on the left, due to a larger development of the front portion of the parietal lobe. It corresponds with a part of the brain called Brodmann area 45 – a zone responsible for our ability to apply words to concepts.

While there are no clear bumps or lines that shout 'genius', however there could well be subtle differences in the symmetry of certain parts of the brain that might yet hint at its owner's cognitive talents.

"Further neuro-imaging and post-mortem studies will have to test and eventually confirm hypotheses relative to the gross and microscopic anatomical substrate of different aspects of exceptional intelligence," write the researchers.

In other words, time will tell if there's more to Descartes' brain than first meets the eye.

There's little doubt the research on any historic brains could be subject to the same criticisms as the studies on Einstein's, meaning we should hold back from reading too much into speculations just yet.

The journey of Descartes' skull makes for an interesting story in its own right, being separated from his body soon after his death, eventually finding its way to the Musée de l'Homme anthropology museum in Paris.

Thing is, there's a small chance the head in the study might not even belong to the respected old philosopher after all.

One thing the research does show is how processes more commonly used on fossils to study their central nervous systems could contribute insights into the brains of more modern figures, even if the squishy bits have long since decayed.

This research was published in Journal of the Neurological Sciences.