Antarctica's Ross Ice Shelf is the world's largest floating slab of ice: It's about the size of Spain, and nearly a kilometre (about 0.6 miles) thick.

The ocean beneath, roughly the volume of the North Sea, is one of the most important but least understood parts of the climate system.

We are part of the multi-disciplinary Aotearoa New Zealand Ross Ice Shelf programme team, and have melted a hole through hundreds of metres of ice to explore this ocean and the ice shelf's vulnerability to climate change.

Our measurements show that this hidden ocean is warming and freshening - but in ways we weren't expecting.

A hidden conveyor belt

All major ice shelves are found around the coast of Antarctica. These massive pieces of ice hold back the land-locked ice sheets that, if freed to melt into the ocean, would raise sea levels and change the face of our world.

An ice shelf is a massive lid of ice that forms when glaciers flow off the land and merge as they float out over the coastal ocean.

Shelves lose ice by either breaking off icebergs or by melting from below. We can see big icebergs from satellites - it is the melting that is hidden.

Because the water flowing underneath the Ross Ice Shelf is cold (minus 1.9 degrees Celsius, or 29 degrees Fahrenheit), it is called a "cold cavity".

If it warms, the future of the shelf and the ice upstream could change dramatically. Yet this hidden ocean is excluded from all present models of future climate.

There has only been one set of measurements of this ocean, made by an international team in the late 1970s. The team made repeated attempts, using several types of drills, over the course of five years.

With this experience and newer, cleaner, technology, we were able to complete our work in a single season.

Our basic understanding is that seawater circulates through the cavity by flowing in at the sea bed as relatively warm, salty water. It eventually finds its way to the shore - except of course this is a shoreline under as much as 800 metres (about 0.5 miles) of ice.

There it starts melting the shelf from beneath and flows across the shelf underside back towards the open ocean.

Peering through a hole in the ice

The New Zealand team – including hot water drillers, glaciologists, biologists, seismologists, oceanographers – worked from November through to January, supported by tracked vehicles and, when ever the notorious local weather permitted, Twin Otter aircraft.

As with all polar oceanography, getting to the ocean is often the most difficult part. In this case, we faced the complex task of melting a bore hole, only 25 centimetres (10 inches) in diameter, through hundreds of metres of ice.

But once the instruments are lowered more than 300 metres (985 feet) down the bore hole, it becomes the easiest oceanography in the world.

You don't get seasick and there is little bio-fouling to corrupt measurements. There is, however, plenty of ice that can freeze up your instruments or freeze the hole shut.

A moving world

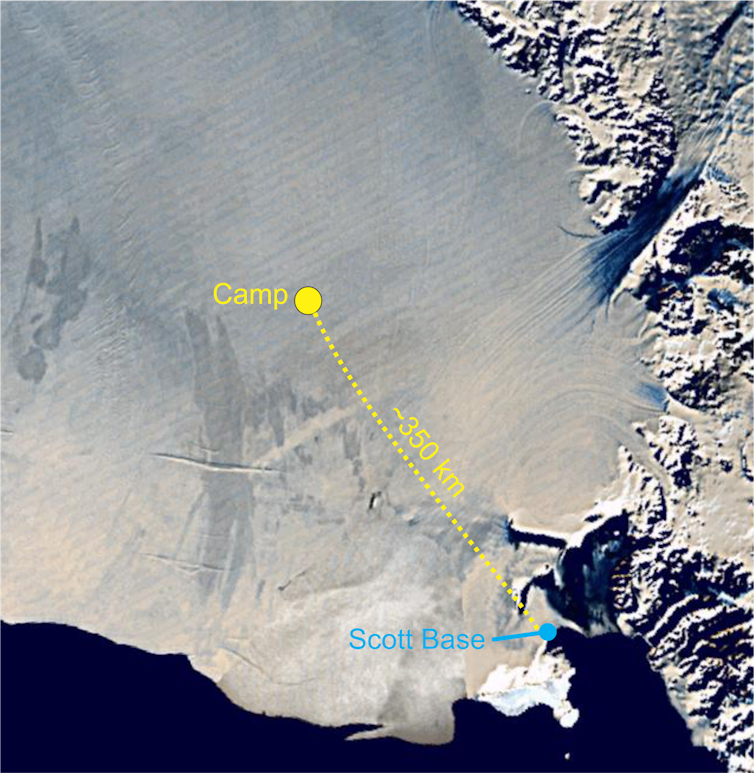

Our camp in the middle of the ice shelf served as a base for this science, but everything was moving.

The ocean is slowly circulating, perhaps renewing every few years. The ice is moving too, at around 1.6 metres (5.2 feet) each day where we were camped.

The whole plate of ice is shifting under its own weight, stretching inexorably toward the ocean fringe of the shelf where it breaks off as sometimes massive icebergs.

The floating plate is also bobbing up and down with the daily tides.

Things also move vertically through the shelf. As the layer stretches toward the front, it thins.

But the shelf can also thicken as new snow piles up on top, or as ocean water freezes onto the bottom. Or it might thin where wind scours away surface snow or relatively warm ocean water melts it from below.

When you add it all up, every particle in the shelf is moving. Indeed, our camp was not so far (about 160 kilometres, or 99 miles) from where Robert Falcon Scott and his two team members were entombed more than a century ago during their return from the South Pole.

Their bodies are now making their way down through the ice and out to the coast.

What the future might hold

If the ocean beneath the ice warms, what does this mean for the Ross Ice Shelf, the massive ice sheet that it holds back, and future sea level?

We took detailed temperature and salinity data to understand how the ocean circulates within the cavity. We can use this data to test and improve computer simulations and to assess if the underside of the ice is melting or actually refreezing and growing.

Our new data indicate an ocean warming compared to the measurements taken during the 1970s, especially deeper down.

As well as this, the ocean has become less salty. Both are in keeping with what we know about the open oceans around Antarctica.

We also discovered that the underside of the ice was rather more complex than we thought. It was covered in ice crystals – something we see in sea ice near ice shelves.

But there was not a massive layer of crystals as seen in the smaller, but very thick, Amery Ice Shelf.

Instead the underside of the ice held clear signatures of sediment, likely incorporated into the ice as the glaciers forming the shelf separated from the coast centuries earlier. The ice crystals must be temporary.

None of this is included in present models of the climate system. Neither the effect of the warm, saline water draining into the cavity, nor the very cold surface waters flowing out, the ice crystals affecting heat transfer to the ice, or the ocean mixing at the ice fronts.

![]() It is not clear if these hidden waters play a significant role in how the world's oceans work, but it is certain that they affect the ice shelf above.

It is not clear if these hidden waters play a significant role in how the world's oceans work, but it is certain that they affect the ice shelf above.

The longevity of ice shelves and their buttressing of Antarctica's massive ice sheets is of paramount concern.

Craig Stevens, Associate Professor in Ocean Physics and Christina Hulbe, Professor and Dean of the School of Surveying (glaciology specialisation).

This article was originally published by The Conversation. Read the original article.