An important cell in mice and humans' immune systems has been shown to have gut-healing properties in mice with a form of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

In a new study, researchers have used the cell to 'trick' the immune system into helping repair damage in the guts of mice, instead of attacking them. They hope to one day target similar intestinal cells in patients with Crohn's or ulcerative colitis.

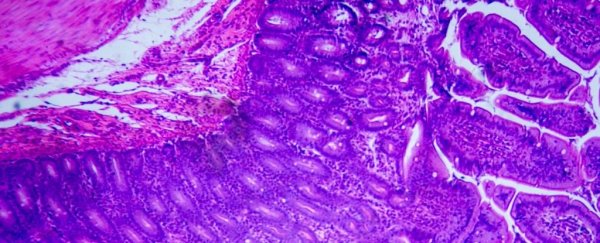

Both of these diseases are caused by the immune system attacking the lining of the gut, and most current medication aims to limit the immune response.

While those medications can help, this blanket approach lumps the good immune players in with the bad, and sometimes, the same player can be a bit of both.

Macrophages, for instance, are known as the 'gatekeepers' of intestinal immunity. This type of white blood cell consumes foreign bodies and plays important roles in inflammation and tissue repair.

Its presence could therefore be essential to stimulating recovery. When researchers looked at macrophages in the intestines of a handful of people with IBD, there was one particular molecule that stood out.

Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) is a messenger molecule in the immune system. It's also linked to tissue regeneration, triggering macrophages that in turn communicate with stem cells in the lining of the gut.

Compared to a database of information on healthy individuals, researchers found the colons of those with IBD showed fewer intestinal macrophages with receptors for prostaglandin (PGE).

These receptors are what receive messages about gut injury, but the signal can't get through to intestinal stem cells if the macrophages can't 'hear' the warning and kickstart the healing process.

"If the patients had acute disease, they had a lower amount of these beneficial cells, and if they went into remission, then amounts of macrophages went up," explains immunologist Gianluca Matteoli at KU Leuven in Flanders, Belgium.

"This suggests that they are part of the reparative process."

If the authors are correct, the findings may represent a new avenue for novel drugs to treat IBD, and while there's still a long way to go before that becomes a reality, initial tests on mice show promising results.

Similar to what was seen in humans, the authors found that animal models with ulcerative colitis did not possess as many macrophages sensitive to prostaglandin compared to healthy controls.

However, if extra prostaglandin was introduced to the gut, the few macrophages sensitive to PGE2 began to stimulate tissue regeneration. When these receptors were knocked out completely, tissue repair once again dropped.

Together, the findings support the emerging perspective that macrophages are major drivers in tissue regeneration following inflammation in the gut. By attaching to receptors on these intestinal white blood cells, PGE2 appears to stop inflammation and promote protective effects.

Unfortunately, scientists don't yet know the exact source of intestinal PGE2, but the fact that macrophages like to eat foreign material makes targeting them with synthetic, prostaglandin-like drugs that much easier.

When the authors enticed intestinal macrophages in the mouse gut to eat up a juicy bubble of stimulating 'medicine', it triggered the secretion of a repair agent, which further stimulated cell proliferation and budding organoids.

This technique of 'feeding' macrophages is often used as an experimental tool, but this is one of the first times it's been used to therapeutic effect.

"We want to identify other factors that trip the switch that turns macrophages from inflammatory cells to non-inflammatory cells," says Matteoli.

"Then… these could be used to target the macrophages and so produce very precise drugs."

The study was published in Gut.