Tiny spoon-shaped implements carried by Roman era Germanic warriors may be evidence they used stimulants on the field of war.

According to a new analysis of the mysterious artifacts and their context, archaeologists and biologists believe that the suspiciously round-ended fittings could have been used to dispense drugs that gave the warriors an edge when they faced their opponents thousands of years ago.

What those drugs actually were is unknown; we'd have to find some evidence of them, such as residues, and that can be challenging after thousands of years have elapsed. But the concept isn't without precedent; and, if it can be validated, the team's hypothesis could reveal evidence of drug use among cultures outside of the Roman Empire.

This would be a big deal: although the use of drugs like opium is well documented in Greece and Rome, the use of narcotics and stimulants in ancient times outside of this region remains a mystery. Historians have previously assumed that the only drug that really saw use by the barbarians was alcohol, at least until much later in history.

Biologists Anna Jarosz-Wilkołazka and Anna Rysiak, and archaeologist Andrzej Jan Kokowski of Maria Curie-Skłodowska University in Poland, thought mysterious spoon-like implements might have been evidence to the contrary.

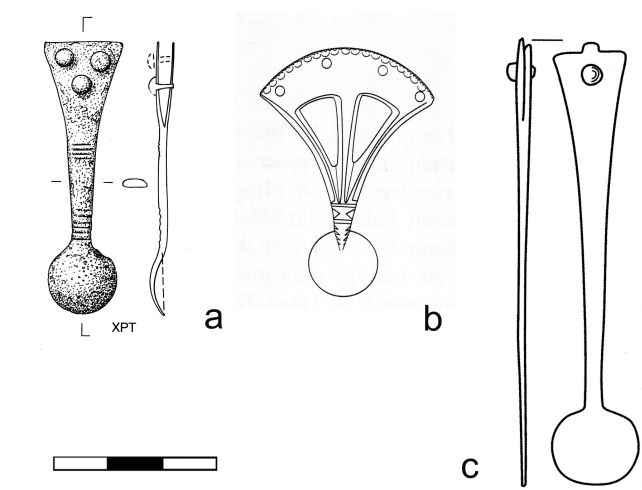

These strange objects keep turning up in the Roman-era burial sites in what are now Scandinavia, Germany, and Poland. Their handles measure 4 to 7 centimeters (1.6 to 2.8 inches) in length, with a bowl or flat disk on one end measuring 1 to 2 centimeters in diameter. They were often attached to the belts of men, but played no role in how the belt functioned.

The team made a careful study of these spoon-like objects, measuring them, studying how they were included in the grave goods, and the context in which they were buried. They cataloged 241 spoons from 116 localities, and made some interesting observations.

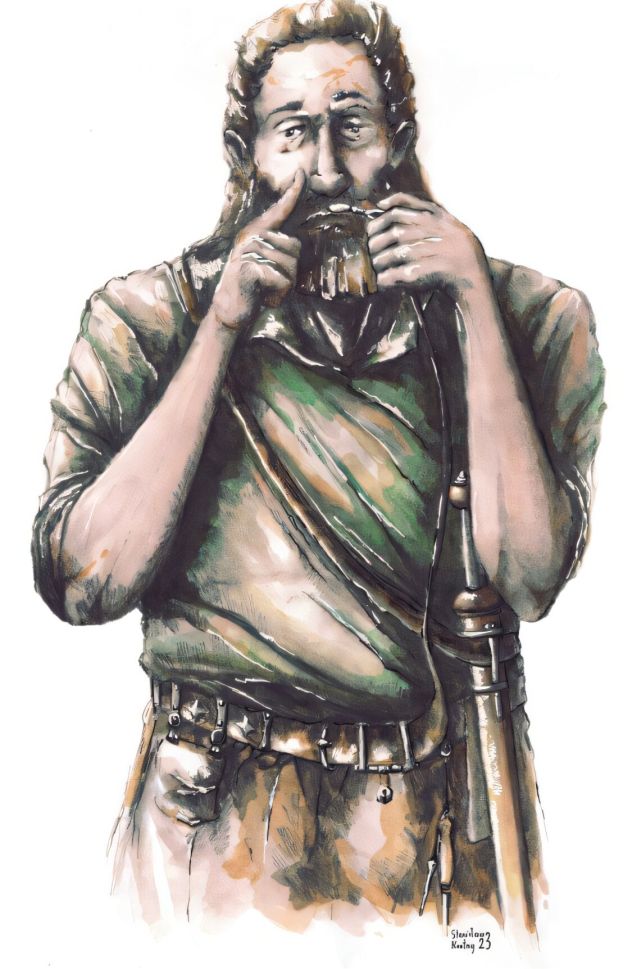

One of the most telling was that the spoons were often included among the accoutrements of war. They were found at war sacrificial sites, directly linking them to warriors; or accompanied by elements of weaponry.

"This," the researchers write in their paper, "allows the thesis to be put forward that this utensil was a common part of a warrior's armor, and from here it is close to concluding that pharmacological stimulation of warriors in the face of stress and exertion was the order of the day."

It's certainly not unheard of. For just a handful of examples, during World War I, cocaine was used liberally. During World War II, both Allied and Axis forces made heavy use of stimulants such as amphetamine and methamphetamine. Between 1966 and 1969, US troops were issued 225 million stimulant pills, including the amphetamine Dexedrine. There are even reports of amphetamine use by Russian soldiers in the ongoing war on Ukraine.

With their thesis established, the researchers then investigated the materials available to the Germanic barbarians which may potentially have been used as stimulants. There were quite a few, including funguses, opium poppy, hops, hemp, henbane, and nightshades such as belladonna and datura.

It's unclear which of these plants, if any, were used by the tribes. But humans have a long history of altering their experience of the world around them with drugs, dating back millennia. It seems unlikely that the Germanic barbarians of the Roman era would have used no drugs whatsoever.

If the team's findings can be confirmed, they will tell us more about how our ancestors lived their lives.

"It seems that the awareness of the effects of various types of natural preparations on the human body entailed knowledge of their occurrence, methods of application," the researchers write, "and the desire to consciously use this wealth for medicinal and ritual purposes."

The analysis has been published in Praehistorische Zeitschrift.