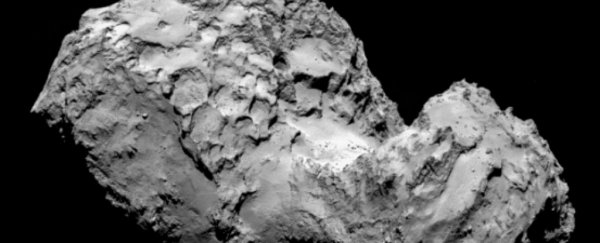

Picture a comet. What colour is it in your mind? If you're like most people, you probably answered white or grey, since we're basically talking about chunks of space ice here. NASA even describes a comet's nucleus as a "dirty snowball".

But this rather common assumption is being challenged by a new study from European Space Agency (ESA) researchers - the team working with the Rosetta spacecraft - which reveals that Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko has been seen changing colour and brightness as it orbits the Sun.

Using Rosetta's Visible and Infrared Thermal Imaging Spectrometer (VIRTIS), the team has been witnessing changes in sunlit parts of the comet since August 2014, a few months after Rosetta started orbiting it. Basically, as the comet travelled towards the Sun, its outer layer changed from a drab, dark red to a bluish colour.

According to the team: "When it arrived, Rosetta found an extremely dark body, reflecting about 6 percent of the visible light falling on it. This is because the majority of the surface is covered with a layer of dark, dry, dust made out of [a] mixture of minerals and organics."

As the comet heated up in orbit, this dust layer was shed off of its surface and was added to its iconic tail. Under this dust layer, lay a centre of bluish ice. This remarkable sight is amplified by the fact that more sunlight makes the comet a whole lot brighter, in some regions by as much as 34 percent.

As Gianrico Filacchione, the study's lead author, reports:

"The overall trend seems to be that there is an increasing water-ice abundance in the comet's surface layers that results in a change in the observed spectral signatures. In that respect, it's like the comet is changing colour in front of our eyes.

This evolution is a direct consequence of the activity occurring on and immediately beneath the comet's surface. The partial removal of the dust layer caused by the start of gaseous activity is the probable cause of the increasing abundance of water ice at the surface."

The study has allowed researchers witness first-hand how orbits and comet activity intersect with each other, and knowing this will be invaluable in further comet research. Although, for us, the takeaway is that we've been picturing comets wrong this whole time.

The team's study was published in Icarus.