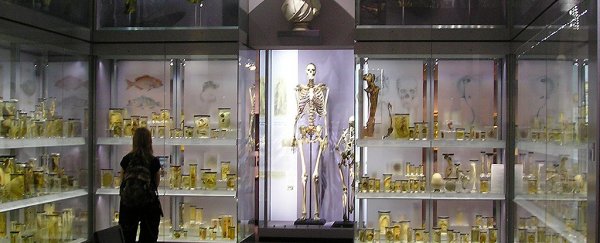

For the past 235 years, a 2.31 metre (7 foot 7 inch) tall skeleton has stood overlooking shelves of pickled cancers, malformed limbs and other assorted medical curiosities in London's Hunterian Museum.

Following a statement by the Royal College of Surgeons, it's possible those bones might at last be laid to rest on the murky bottom of the English Channel, fulfilling the dying wishes of an 18th century man known throughout the land as the Irish Giant.

Charles Byrne was born in 1761 with the condition acromegalic gigantism, a pituitary disorder that saw him grow to an extraordinary size.

In his late teens he set off for fame and fortune, making his way from the sleepy Irish village of his birth to London's show houses.

To the public he was a curiosity worth a shilling or two to see. To the anatomists of his day, Byrne was a prize specimen; an intriguing collectable begging for an exploratory dissection.

None hungered more for Byrne's bones than the Scottish surgeon, John Hunter. The reputable medical researcher had an insatiable lust for all things peculiar, whether it was in the form of rare deformities or exotic animals from far off lands.

Part Dr Dolittle, part Dr Jekyll – and, just possibly, part Mr Hyde – the anatomist made it no secret that he had intentions to get his hands on the body of Charles Byrne, should the day come that the giant no longer had need of it himself.

Sadly, that moment came far sooner than Byrne might have liked. On 1 June, 1783, aged just 22, the Irish Giant passed away following months of failing health.

A newspaper at the time described the scene outside his residence once news got out, writing, "The whole tribe of surgeons put in a claim for the poor, departed Irish Giant, and surrounded his house just as Greenland harpooners would an enormous whale".

By some accounts, Byrne had left instructions that his remains should to be taken to the sea in a weighted coffin and sunk to the bottom to put his extraordinary body out of reach of dissection.

His closest friends found him an appropriately sized coffin, and even made a few shillings by putting the large box on public display. After a few days they carried their friend to the seaside town of Margate.

Somewhere between their starting point and their destination, the body of Charles Byrne was removed and replaced with a load of rocks, possibly while his funeral party paused for a beverage on the way.

The details are speculative, with researchers left to glean what they can from questionable newspaper reports. But one thing is certain – John Hunter succeeded in getting his hands on his whale.

Those bones, stripped of flesh and boiled white, have remained in his museum ever since, though not without controversy.

For years, Thomas Muinzer from the University of Sterling has petitioned the curators of the Hunterian Museum to respect Byrne's alleged wishes and put his body to rest.

The call has long fallen on deaf ears. Samuel Alberti, past director of the Hunterian Museum, once cited benefits of education and alleged wishes of Byrne's ancestors as reason to keep the bones on display.

"The Royal College of Surgeons believes that the value of Charles Byrne's remains, to living and future communities, currently outweighs the benefits of carrying out Byrne's apparent request to dispose of his remains at sea," Alberti told The Guardian in 2011.

Times have changed, and there is now a glimmer of hope for Byrne's old bones. With the closing of the museum for refurbishment, there's word that the Irish Giant won't be there when the place opens again in three years' time.

"The Hunterian Museum will be closed until 2021 and Charles Byrne's skeleton is not currently on display," state the Royal College of Surgeons.

"The Board of Trustees of the Hunterian Collection will be discussing the matter during the period of closure of the museum."

That's not to say his interment is a certainty, let alone a burial at sea. But given his wish to be put well out of reach of any researchers, there's every possibility we'll see a change of heart.

Historical remains such as those of the Irish Giant can have a place in research and as an attraction of public interest. But there are ethical quandaries involved when we deal with bodies and body parts with a contested history, especially when familial connections stretch across time.

Recent DNA analysis on Byrne's remains have opened the way for possible ancestral links to form between the man and living relatives, further complicating his case.

Museums and research bodies around the world often struggle with the choice of repatriating anthropologically significant remains or holding onto them in the expectation that future science might have further need of them.

In the sad case of Charles Byrne, it's high time that we say "sorry we kept you so long", and give him the peace at sea he so desperately wanted.