Jurassic Park's most iconic scenes should have run a little slower, based on new research suggesting our favourite dinosaur, Tyrannosaurus rex, couldn't manage more than a walk.

Calculating the top speed of the tyrant lizard king seems to be an obsession for paleontologists, who have debated over the decades whether the giant predator was a sprinter or a stroller. It turns out that while T. rex could still take quick steps, any serious gait would leave it with more than just a bad case of shin splints.

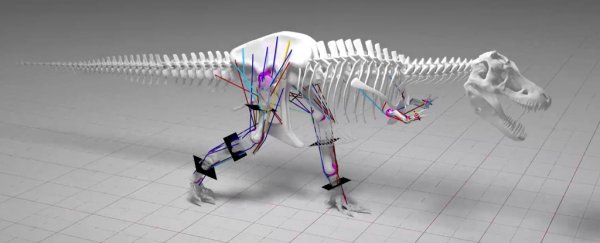

The research, led by scientists from the University of Manchester in the UK, created a detailed computer model that used multibody system dynamics – which looks at connected solid objects – to analyse the bends and twists applied to different parts of a skeleton.

Their model rex was based on a specimen dug up in 1987 called BHI 3033, also known as Stan to his pals.

CT scans of various fossils provided limits the team could work with to decide the kinds of forces bones could take before they were damaged.

Working out the mass of any dinosaur isn't without its challenges, but the researchers settled on a conservative 7206.7 kilograms (about 15,900 pounds) of meat and bone for their calculations.

From there it was a matter of determining the forces of impact bones would experience as the dinosaur built up speed, taking into account hypothetical soft tissues that could cushion the blow.

Speeds above 27.7 kilometres (17 miles) per hour would have pushed the limits on Stan's bones, which were estimated to have a yield strength of about 200 megapascals (29,000 psi).

For comparison, average human walking speed is around 4.8 km/h (3mph), jogging speed is around 8-9km/h (5-6mph), and Usain Bolt can run 100m in roughly 38km/h (23.7mph).

A more reasonable estimate on bone strength, according to the researchers, would be around half that 27.7 km/h at the upper limit, putting our buddy Stan in the ballpark of someone sprinting to catch a bus.

"Therefore, even if safety factors below the lower limit seen in living animals are allowed, our analysis demonstrates that T. rex was not mechanically capable of true running gaits," the researchers write in their report.

Estimates on an adult T. rex's maximum velocity have ranged in the past have looked at everything from body configurations and muscle attachments to their fossilised footprints, with estimates ranging from 18 km/h (11.2mph) to a very speedy 54km/h (33.6mph).

This research puts some constraints on those higher estimates, suggesting T. rex could still take some quick steps with those long limbs, but couldn't break into a sprint that would chase down Jeff Goldblum in a jeep.

"Here we present a new approach that combines two separate biomechanical techniques to demonstrate that true running gaits would probably lead to unacceptably high skeletal loads in T. rex," says lead researcher William Sellers from the University of Manchester.

That means the big Tyrannosaur would never have been airborne as it leaped from foot to foot, keeping its speed down to a minimum.

A slower T. rex might make for less thrilling blockbusters, but it could help us understand how the dinosaur's hunting behaviour shifted as it evolved.

Bigger predators can take down prey that would usually have size on their side, meaning high speed wouldn't need to be an issue.

But what of junior Tyrannosaur rex? Could they have been agile sprinters? The model suggests possibly not, but more research would be needed to validate the idea.

Although limited to T. rex in this study, there's no reason the same model couldn't be applied to any other long-extinct creature we're curious about.

"Tyrannosaurus rex is one of the largest bipedal animals to have ever evolved and walked the Earth," says Sellers.

"So it represents a useful model for understanding the biomechanics of other similar animals."

We still don't advocate trying to outrun a T.rex if ever given the opportunity, but it might help knowing if you get your running shoes on, Stan might not risk the leg pain.

This research was published in Peer J.