An aerial survey of Antarctica's largest ice-free region, which was presumed to be dry, has revealed interconnected aquifers beneath the glaciers and permafrost.

The international team of researchers that made the discovery says the briny liquid, which has twice the salt content of seawater, is about 300 metres underground. And while it's well below freezing, they say it's possible the groundwater is harbouring some very hardy species of microbes.

The results, which were published in the journal Nature Communications, could help researchers understand how life can evolve and persist in extreme habitats on Earth, and possibly on Mars, where another research team - using data collected by NASA's Curiosity Rover - recently confirmed the presence of pockets of very salty water near its equator.

"The subsurface aquifers that we've been looking at in the [Antarctic] are potential analogues to understanding Mars systems," lead author and microbiologist Jill Mikucki, from the University of Tennessee, Knoxville in the US, told Irene Klotz at Discovery News.

Mikucki was part of a team that recently collected samples from Antarctica's Blood Falls, which are the only known manifestation of these underground systems of briny water at the surface, and have shown signs of microbial life.

"If Blood Falls brine is representative of the subsurface fluid observed… [then] an extensive ecosystem exists below the Taylor Glacier and much of Taylor Valley," the researchers write.

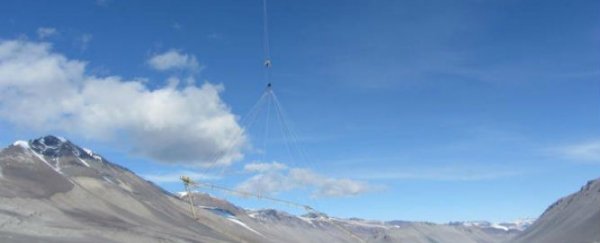

To find their aquifers, the researchers used a novel electromagnetic mapping system called SkyTEM, which can produce images of subsurface environments.

The team attached this system to a helicopter, which was flown over a portion of the McMurdo Dry Valleys - the largest ice-free region in Antarctica and one of the world's most extreme deserts.

At 4,800 square kilometres (or 1,900 square miles) it's larger than about 70 sovereign countries and territories, yet it comprises only 0.03 percent of the Antarctic landmass.

The team conducted its survey over an area of 295 square kilometres, and measured the electrical resistivity beneath the gravel and frozen soil.

As Klotz explains for Discovery News, "liquids - particularly salty liquids - are more conductive than rock, soil and ice, giving scientists the ability to differentiate subsurface materials."

The team detected low subsurface resistivity, which was inconsistent with the high resistivity of glacial ice, and with that of the dry permafrost in the region.

"We interpret these results as an indication that liquid, with sufficiently high solute content, exists at temperatures well below freezing and considered within the range suitable for microbial life," the team writes in their paper.

They say there's evidence to suggest the presence of two interconnected aquifers beneath glaciers, lakes and permafrost, with one stretching for nearly 18 kilometres.

Researchers know that subglacial water is widespread across the icy continent, with at least half of the areas covered by the Antarctic ice sheet harbouring water systems underneath them, which are comparable to lakes and wetlands on warmer continents.

But until now, scientists didn't know very much about groundwater in areas of Antarctica that weren't covered in ice.

Finally, they have their first clues.

"It suggests that this ecosystem is extensive and connected. There could be a very, very large subsurface habitable environment throughout the Antarctic regions," co-author and ecologist Ross Virginia, from Dartmouth College in the US, told Klotz.

"One of the big questions now is this finding regionally specific, or are there many locations in Antarctica where we have conditions that have created these subsurface environments for life," he adds.

Source: Discovery News