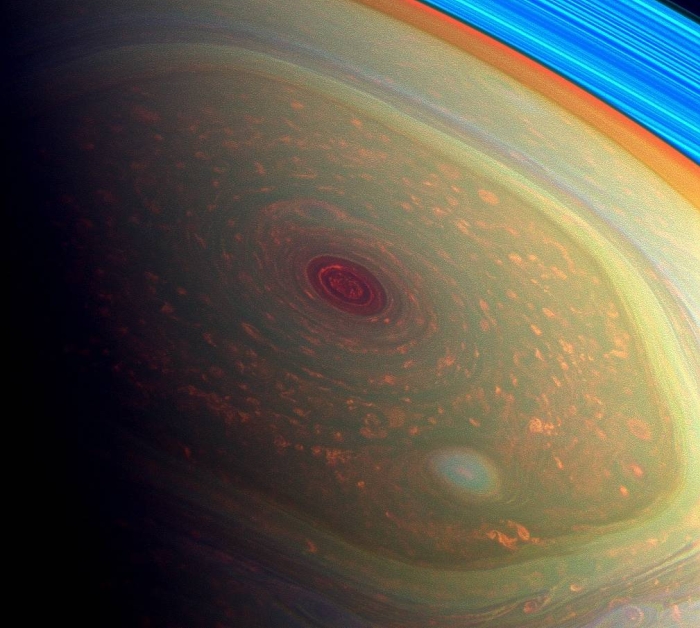

There's something strange over Saturn's north pole. A tremendous structure towering high above the clouds indicates that the planet's peculiar hexagonal formation is much, much bigger than was initially apparent.

The data comes from Cassini, which, a year after its demise plunging into Saturn's opaque atmosphere, is still leading us to new discoveries.

When the probe commenced its observations in 2004, during the southern summer it clocked a warm high-altitude vortex over the planet's south pole. Meanwhile, Saturn's north pole contains a famous hexagonal cloud pattern, but we didn't think it had a vortex - until now.

A long-term study has found a similar vortex forming over the north pole as the north approaches summer, high up in the stratosphere. And, just like the jet-stream below it, the vortex is hexagonal.

"The edges of this newly-found vortex appear to be hexagonal, precisely matching a famous and bizarre hexagonal cloud pattern we see deeper down in Saturn's atmosphere," said planetary scientist Leigh Fletcher of the University of Leicester in the UK.

"While we did expect to see a vortex of some kind at Saturn's north pole as it grew warmer, its shape is really surprising. Either a hexagon has spawned spontaneously and identically at two different altitudes, one lower in the clouds and one high in the stratosphere, or the hexagon is in fact a towering structure spanning a vertical range of several hundred kilometres."

Ever since its discovery in the early 1980s by the Voyager spacecraft, the hexagon has been a puzzle for planetary scientists. It wasn't until 2006 that Cassini got a good photo of it - and scientists have been trying to figure out more about it ever since.

The structure is strangely symmetrical, and is made by an atmospheric jet stream with winds blowing up to 500 kilometres per hour (300 miles per hour). And it's huge - measuring a massive 30,000 kilometres (20,000 miles) across. Earth has a diameter of 12,742 kilometres (7,917.5 miles) - two Earths could fit inside the hexagon, with room to spare.

(NASA/JPL-Caltech/SSI)

(NASA/JPL-Caltech/SSI)

It also rotates at roughly the same rate as the planet itself, indicating that the structure is tied to the planet's rotation, much like the polar front jet stream here on Earth. And a previous investigation found that, using rotation, the hexagon shape could be replicated in fluid in a lab.

Cassini studied the hexagon in detail using its Composite Infrared Spectrometer (CIRS) in 2006. At this point, it was still northern winter on Saturn - its year is around 30 Earth years, so its summers and winters are long - which meant the north pole was in shadow. But CIRS could circumvent this hurdle, since it can observe thermal radiation.

However, the upper atmosphere was still too cold for reliable infrared observations, so Cassini confined itself to studying the cloud layer. But in 2009, Saturn's north pole started to emerge from winter, the atmosphere warmed, and things turned around.

"We were able to use the CIRS instrument to explore the northern stratosphere for the first time, from 2014 onwards," said planetary scientist Sandrine Guerlet of the Laboratoire de Météorologie Dynamique in France.

"As the polar vortex became more and more visible, we noticed it had hexagonal edges, and realised that we were seeing the pre-existing hexagon at much higher altitudes than previously thought."

It towered hundreds of kilometres over the clouds, and showed quite different behaviour from the southern vortex. It's cooler, not as mature, and, of course, the south pole has no hexagon. But since wind conditions change dramatically with altitude, the fact that the hexagon shape persists so much higher than the cloud tops is a baffling conundrum.

"One way that wave 'information' can leak upwards is via a process called evanescence, where the strength of a wave decays with height but is just about strong enough to still persist up into the stratosphere," said Fletcher.

"We simply need to know more. It's quite frustrating that we only discovered this stratospheric hexagon right at the end of Cassini's lifespan."

Saturn's northern summer has already peaked, with the solstice occurring in May 2017 (prior to which the hexagon mysteriously changed colour). However, there are still several years left of summer, and its expected that the north pole vortex will continue to develop.

However, with Cassini's mission ended, it's uncertain whether scientists will be able to observe these changes.

"The Cassini spacecraft continued to provide new insights and discoveries right up to the very end. Without a capable spacecraft like Cassini, these mysteries would have remained unexplored," said Cassini scientist Nicolas Altobelli of the European Space Agency.

"It shows just what can be accomplished by an international team sending a sophisticated robotic explorer to a previously unexplored destination - with results that keep flowing even when the mission itself has ended."

The team's research has been published in the journal Nature Communications.