In the guts of an ancient mummified crocodile, researchers have discovered a telltale bronze hook.

Up to 3,000 years ago, the 2.2-meter (7.2-foot) long crocodile died before it had even begun to digest a fish found intact around the hook in its stomach.

The human-made object and state of the carefully preserved animal suggest it was deliberately caught in the wild and processed as an offering to the Egyptian crocodile god, Sobek.

Luckily, the ancient Egyptians who prepared the croc's body for mummification didn't remove its guts, as was common practice for human mummies. This allowed a UK team of researchers to reveal what was frozen in time inside.

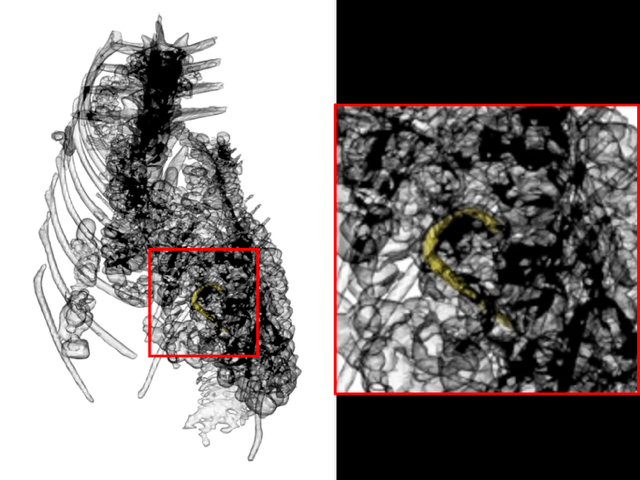

"Whereas earlier studies favored invasive techniques such as unwrapping and autopsy, 3D radiography provides the ability to see inside without damaging these important and fascinating artifacts," explains University of Manchester archaeozoologist Lidija McKnight.

Scans revealed the stones the large reptile (now known as crocodile mummy 2005.335) had swallowed to aid its troubled digestion hadn't yet reached their destination in its stomach, either.

Another un-eviscerated crocodile mummy studied in 2019 was found in a similar condition, with a stomach still full of eggs, a rodent, an insect, and the remains of fish bones and feathers.

The researchers suspect the short time frames between these crocs' last meals and deaths mean they were intentionally caught – hunted specifically for a religious ritual.

Ancient Egyptians worshiped the large reptiles as representatives of Sobek, lord of the Nile. As top predators, crocodiles were respected for the threat they posed, and their symbols were thought to ward off danger and protect places from negative influences.

But they were also seen as a sign of fertility, possibly due to the contrasting gentle care these vicious hunters show their young. So healthy crocodile populations were considered good omens for thriving agriculture.

Crocs were far from the only animals ancient Egyptians mummified. From scarab beetles to ibis and puppies, estimates suggest up to 70 million animals were sacrificed as offerings to their gods.

Using their noninvasive techniques, McKnight and her team were able to virtually recreate the human-made hook hidden inside the fish, inside the crocodile. They then crafted an accurate replica for use in museum displays.

"The Egyptians probably used a hardened clay mold into which the molten metal, melted over a charcoal-based heat source, would have been poured. Despite the passing of several millennia between the production of the ancient fish hook and the modern replica, the casting process remains remarkably similar," explains McKnight.

"Mummies have long been a source of fascination for museum visitors of all ages. Our work provides a unique opportunity to connect visitors to the story of this animal."

This research was published in Digital Applications in Archaeology and Cultural Heritage.