Scientists have identified the aromatic ancient recipe that preserved an Egyptian noblewoman who was mummified around 1450 BCE, meticulously recreating 'the scent of eternity'.

Advances in chemical analysis technology enabled detection of individual substances in balm residue from once-sealed canopic jars that stored the mummified organs.

In ancient Egypt, mummification was the ultimate art form for preserving the dearly departed for nearly 4000 years, part of intricate burial practices that we know of thanks to artifacts left behind.

Although ancient Egyptian texts are fascinating, there are few written sources addressing this sacred process, and those that do have left us in the dark about the recipe's specifics.

"'The scent of eternity' represents more than just the aroma of the mummification process," notes archaeologist Barbara Huber from Germany's Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology.

"It embodies the rich cultural, historical, and spiritual significance of Ancient Egyptian mortuary practices."

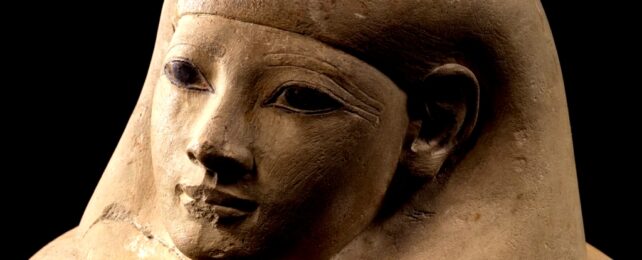

Serving as the wet nurse to Pharaoh Amenhotep II, the noblewoman's elite status was evident from her title 'Ornament of the King' and her presence in a royal tomb in the Valley of the Kings. It was also echoed in the complexity of the balms that preserved her organs in four separate jars.

Named Senetnay, the ancient figure has posed a mystery waiting to be unraveled since the jars were excavated in 1900 CE.

Huber and colleagues used a combination of gas chromatography and mass spectrometry to examine six balm samples from two of the jars, which once stored Senetnay's lungs and liver. Their results indicate balms of more elaborate composition than those used on other mummies from the same time period.

Beeswax, plant oils, rich animal fats, naturally occurring bitumen, and resins sourced from coniferous trees, according to Huber and team, are the secrets to her well-preserved mummy. In an aromatic twist, they also found coumarin, a plant-sourced compound that lends a delightful vanilla-like scent to the mix.

"Previous analyses suggests that ancient Egyptian mummification balms contained a limited range of ingredients before the Third Intermediate Period (c. 1000 BCE), becoming more complex through time," the authors write.

The team also discovered diversity in the ratios of the substances in each jar that held Senetnay's organs. And the jar that had housed Senetnay's lungs contained two ingredients not found in the other, a one-of-a-kind brew suggesting the concoction was tailored to individual organs.

Consistent with the traits of a high-ranking woman, it seems many ingredients in Senetnay's balms required transport from exotic locations outside Egypt.

One unique, lung-balming substance is larixol, from the resin of larch conifers. Another fragrant resin detected is possibly dammar from dipterocarp trees found in India and southeast Asia, or a resin from Pistacia trees, native to the Mediterranean coast.

"These complex and diverse ingredients, unique to this early time period, offer a novel understanding of the sophisticated mummification practices and Egypt's far-reaching trade-routes," says Egyptologist Christian Loeben from the Museum August Kestner in Germany.

Since the samples are 3,500 years old, researchers can't rule out the possibility of degradation processes, or unevenly mixed or distributed balm causing the ingredient variances between jars. However, other recent mummification findings support their hypothesis of organ-specific recipes.

"Analytical chemistry is able to shed significant light on the identification of ingredients included in ancient balms, adding substantially to information recoverable from ancient textual sources," the team writes.

An upcoming exhibit at Denmark's Moesgaard Museum will feature the recreated ancient aroma, giving visitors a rare chance to take a sniff back in time.

The study has been published in Scientific Reports.