A new study has found that schizophrenia could originate as early as the first 12 weeks of pregnancy, which means we might be able to eventually treat it in utero before birth.

By growing "mini brains" in lab conditions, scientists have been able to identify disruptions in stem cells surrounding the ventricles, or brain cavities, as early as two weeks into the growth – the equivalent of the first trimester of pregnancy.

According to the team of researchers, this is a major step forward in understanding the biological origins of the brain disorder, which was first described in an ancient Egyptian medical text called the Ebers Papyrus back in 1550 BCE.

"This disease has been mischaracterised for 4,000 years," says one of the researchers, Michal K. Stachowiak from the State University of New York at Buffalo.

"We finally now have evidence that schizophrenia is a disorder that results from a fundamental alteration in the formation and structure of the brain."

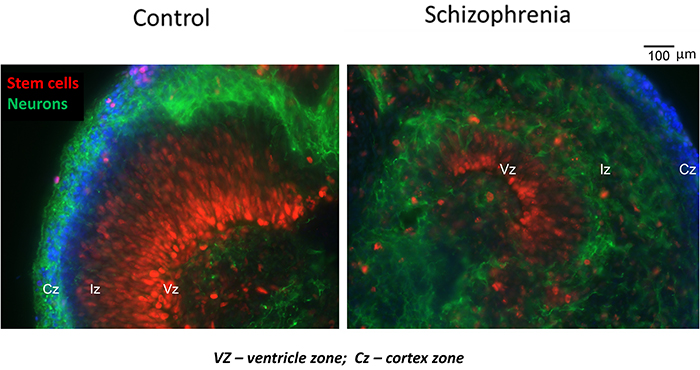

Disrupted stem cells (in red) in schizophrenia samples (right). (M. Stachowiak)

Disrupted stem cells (in red) in schizophrenia samples (right). (M. Stachowiak)

The team grew what are known as cerebral organoids, miniature organs resembling the brain, using reprogrammed skin cells from three people with schizophrenia and four people without that were acting as a control group.

Fed with the right nutrients, acids, and glucose, these mini brains can grow to create neuroectoderm, the tissue that forms our brains. Eventually, brain ventricles, a cortex, and a region similar to the brain stem appear.

"The goal was to, in a sense, recapitulate important stages in brain formation that take place in the womb," says Stachowiak.

As the tiny brain models began to take shape, the scientists noticed abnormalities in the organoids developed from patients with schizophrenia: the neural progenitor cells that go on to form neurons weren't properly distributed, and very few mature neurons ended up appearing in the cortex.

That matches previous research in which schizophrenia has been linked to a breakdown in the functioning of the cortex, where the brain handles important stuff like memory, attention, and language processing.

"Our research shows that the disease likely starts during the first trimester and involves accelerated cell divisions, excessive migration and premature differentiation of the neuroectodermal cells into neurons," says Stachowiak.

"Neurons that connect different regions of the cortex, the so-called interneurons, become misdirected in the schizophrenia cortex, causing cortical regions to be misconnected, like an improperly wired computer."

Now that we've spotted this faulty wiring at such an early stage of the brain's development, the next step is to work out ways it could be treated. A faulty genomic pathway called the Integrative Nuclear FGFR 1 Signaling (INFS) pathway, the subject of earlier research, could hold the key.

Maybe drugs or dietary supplements could be given to pregnant women where a risk of schizophrenia has been identified, suggest the researchers, though for now it's very early days for working out how to make use of this new data.

Symptoms of schizophrenia usually appear in adolescence or young adulthood, and the disorder is estimated to affect more than 21 million people worldwide, causing severe problems with thought processes, perception, and a sense of self.

While the condition can be managed with drugs, there's no cure: but researchers continue to learn more about the genetic roots of the disorder and exactly how it messes with the wiring inside the brain. Now we have more information about just when it starts, too.

"We now can state that schizophrenia is a disorder of faulty brain construction that occurs early in development, corresponding to the first trimester, and involving specific malformation of neuronal circuits in the cortex," says Stachowiak.

The findings have been published in Translational Psychiatry.