Scientists have developed an artificial thymus, an organ crucial to the human immune system, that could produce special cancer-fighting T-cells in the body on demand.

T-cells are white blood cells that naturally combat disease as part of our immune system, but these artificially engineered versions would be targeted at specific forms of cancer, potentially giving our natural defences a boost in attacking the disease.

In the human body, the thymus sits in front of the heart and uses blood stem cells to make T-cells, which then go onto fight infection in the body. But as people get older or become sick, the thymus becomes less efficient.

In tests, the team from the University of California, Los Angeles was able to use its artificial thymus to turn blood stem cells into T-cells that attacked cancerous growths while leaving healthy tissue alone. You can think of is like a bionic thymus with extra powers.

What's more, our normal T-cells can get worn out by fast-growing cancers, and certain types of the disease can evade T-cell attacks too, and so some artificial assistance would be most welcome.

In the natural process inside our bodies, T-cells produced by the thymus are given specialised molecules, called receptors, which act as guides towards cells infected by viruses or cancers.

Scientists have been able to add cancer-seeking receptors to T-cells for several years now, in a process known as adoptive T-cell immunotherapy – an approach that has been very successful so far, even if it's still in the early stages of testing.

T-cells are collected from patients, reprogrammed with the right receptors, then transfused back into the body.

The only problems – which this new research tries to fix – are that the process is time-consuming, and relies on the patient having enough T-cells to make use of in the first place.

That's where the artificial thymus developed at UCLA comes in, which could pump out cancer-fighting T-cells from stem cells or donated blood more quickly than the existing methods.

"We know that the key to creating a consistent and safe supply of cancer-fighting T-cells would be to control the process in a way that deactivates all T-cell receptors in the transplanted cells, except for the cancer-fighting receptors," says one of the team, Gay Crooks.

That's important because if cells are produced from stem cells and aren't taken from the patients themselves, there's a chance they could be rejected once they're in the body.

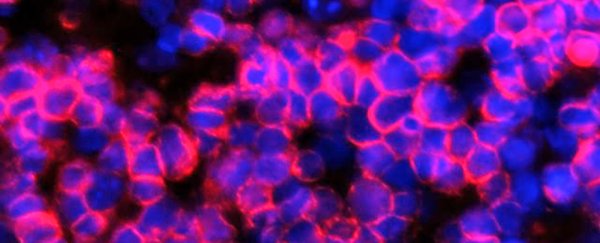

However, in lab tests the researchers were able to engineer their artificial thymic organoids to produce T-cells that worked similarly to those naturally produced by the thymus, and which had only the cancer-fighting receptors in them.

Even better, the team says its work can be easily reproduced by other scientists, so we have a foundation for developing a cancer-fighting mechanism that's fast, effective, and in line with the body's existing defences.

We'll definitely be keeping a close eye on this research as it develops.

The findings have been published in Nature Methods.