There are now 22 of them, and we still have no idea what they are, what they mean, or where in the Universe they come from - fast radio bursts, those brilliant bursts of energy that last mere milliseconds, but are a billion times more luminous than anything we've seen in our galaxy.

The latest fast radio burst ( FRB) that's been detected might be the most confounding one yet - after looking at it through the lens of every telescope they can get their hands on, scientists say they're no close to solving the mystery.

"We spent a lot of time with a lot of telescopes to find anything associated with it," the study's first author, Emily Petroff from the Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy, told Ryan F. Mandelbaum at Gizmodo.

"We got new wavelength windows we've never gotten before. We're still trying to figure out where this one came from."

FRBs are some of the most mysterious and explosive signals in the Universe, and they've been associated with everything from microwaves to alien spaceships.

With just 22 of these signals confirmed to date, they might seem rare, but scientists think they're actually quite common in the Universe - it's predicted that around 2,000 of these things are lighting up the Universe every single day.

The reason we have such a tough time finding them is because they last for around 5 milliseconds before they're gone, and it wasn't until earlier this year that scientists were even able to confirm that they came from space - and not some Earth-based interference.

But the fact that they come from space is about as far as we've gotten in terms of characterising these things.

A new paper has just come out describing a fast radio burst, called FRB 150215, which was detected in real time by the Parkes radio telescope in Australia on 15 February 2015.

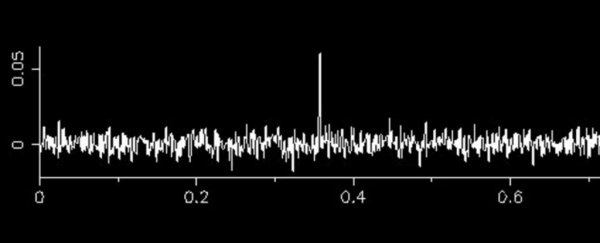

Here it is in all its glory - a big, fat blip:

The first reason this burst is weird, and unlike any other FRBs that have been detected to date, is that Petroff and her team were able to view it through several telescopes around the world, but were unable to detect any kind of signal or trace of light left behind.

"The burst was followed up with 11 telescopes to search for radio, optical, X-ray, gamma-ray, and neutrino emission," the researchers report.

"Neither transient nor variable emission was found to be associated with the burst, and no repeat pulses have been observed in 17.25 hours of observing."

How can something with that generates as much energy as 500 million Suns have no afterglow?

The second reason FRB 150215 is weird is that it really shouldn't have been detectable from Earth given the direction in space it was coming from - it had to pass through an extremely dense region of the Milky Way in order to get to us.

As Petroff explains on Twitter, something they have been able to measure in FRB 150215 is its polarisation, "which is really hard to get".

One aspect of measuring this polarisation - a quantity called Rotation Measure (RM) - actually tipped the team off to where in the Milky Way the signal passed through.

In such a dense area of space, the team was expecting lots of magnetic interference, and hence a high RM, but they got the exact opposite:

For FRB 150215? The RM = 0 😯

— Dr. Emily Petroff (@ebpetroff) May 9, 2017

Surprising, because the FRB went through a dense line through the Milky Way, so there should be *some* RM!

Turns out, the researchers got extremely lucky with this one, because it happened to pass through "some kind of hole" of the Milky Way that also had an RM of zero.

As for where we go now, the trick to cracking the FRB code seems to be sample size - we still only have 22 of them, and scientists are going to need a whole lot more to figure out where they're coming from.

We should also point out that their paper is yet to be peer-reviewed, so interpretations as they stand could change as more researchers in the field get their hands on the data - and more strangeness could also ensue in the coming months.

As Petroff points out to Gizmodo, "It's not very often in science that you get to work on something that's so brand new and so unknown that you get to answer the fundamental questions."

Oh and that suggestion from earlier this year that fast radio bursts could be powering alien spaceships? Petroff has an opinion on that too.

The research has been published at the pre-print website, arXiv.org.