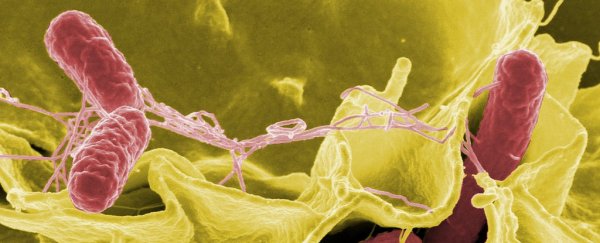

Salmonella is commonly linked to fevers and food poisoning, and generally speaking, it isn't good news at all for your body. But scientists have come up with an exception: a genetically engineered form of Salmonella bacteria that can eat away at cancer tumours.

The modified bacteria target tumours in the brain rather than seeking out the human gut where Salmonella usually causes damage – and the technique could lead to a highly targeted technique of fighting one of the worst types of cancer there is.

Researchers from Duke University gave the treatment to rats with the aggressive brain cancer glioblastoma, and saw significant increases in lifespans, with 20 percent of the rodents surviving an extra 100 days compared to control animals – the equivalent of 10 years in human terms.

"Since glioblastoma is so aggressive and difficult to treat, any change in the median survival rate is a big deal," says one of the team, Johnathan Lyon.

"And since few survive a glioblastoma diagnosis indefinitely, a 20 percent effective cure rate is phenomenal and very encouraging."

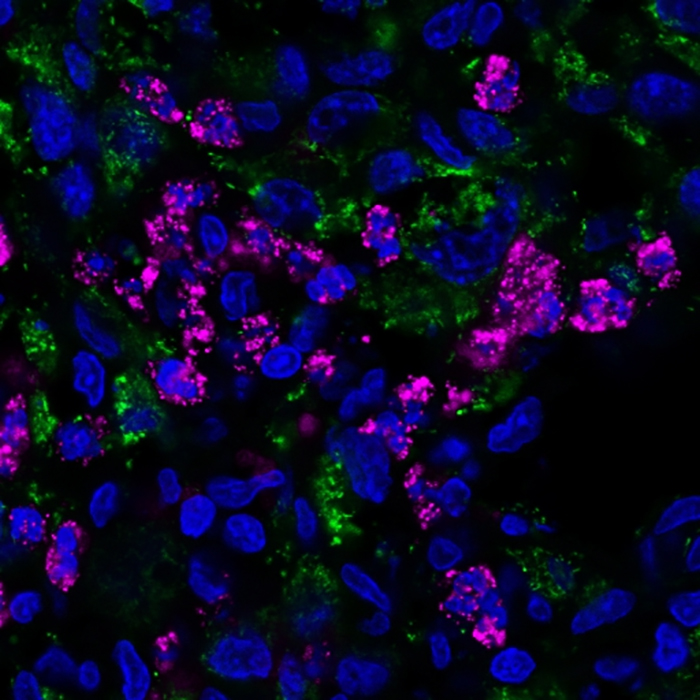

Bacteria (pink) take hold of cancer cells (blue). Credit: Duke University

Bacteria (pink) take hold of cancer cells (blue). Credit: Duke University

It's a promising direction of study, since survival rates of humans with this cancer are pretty bleak. Only about 30 percent of patients with glioblastoma live for more than two years after diagnosis.

Part of what makes it so hard to treat is that the tumours hide behind the blood-brain barrier, which separates the circulating blood from the brain's own fluid.

Conventional drugs can't easily reach through this membrane, so a more targeted approach is needed to stop glioblastoma from thriving.

To achieve this, the researchers used a genetically adjusted and detoxified form of Salmonella typhimurium, modified to be deficient in a crucial organic compound called purine.

Glioblastoma tumours are an abundant source of this enzyme, which induces the bacteria to seek out the cancer cells to get the purine that they need.

And when the bacteria get to the tumours, two more genetic tweaks kick into action.

Because cancerous cells multiply so quickly, oxygen is scarce inside and around tumours. Knowing this, the scientists coded their Salmonella to produce two proteins called Azurin and p53 in the presence of low levels of oxygen.

These compounds instruct the cancer cells to effectively self-destruct, so the end result is like a genetically-coded guided missile, seeking out the tumour and blitzing cancerous cells when it arrives.

The researchers say the technique is much more accurate than surgery, and because the bacteria are otherwise detoxified, there should be no damaging side effects for the patient.

Of course, having success with a group of rats is no guarantee that the treatment will translate to the human body, but the researchers are hopeful that the technique can be developed to treat cancer patients in the future.

The first step is to get that 20 percent success rate up. Based on initial tests, the 80 percent of cases where the treatment had no effect could be down to the tumour cells outpacing the bacteria, or inconsistencies in the Salmonella's penetration in the body.

"It might just be a case of needing to monitor the treatment's progression and provide more doses at crucial points in the cancer's development," says Lyon.

"However, this was our first attempt at designing such a therapy, and there is some nuance to the specific model we used, thus more experiments are needed to know for sure."

The research has been published in Molecular Therapy Oncolytics.