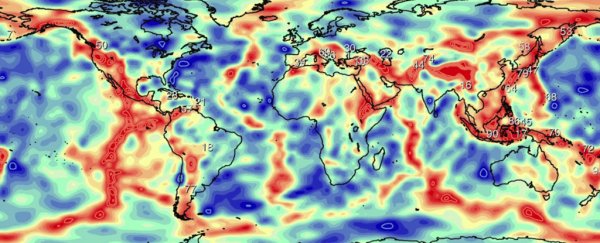

For as long as humans have been around we've been fascinated by the world hiding underneath the surface of the Earth, and now scientists are systematically mapping the positions of the tectonic plates that have been pushed deeper into the planet's core.

It's called the Atlas of the Underworld and you can view it online – measurements go down up to 2,900 kilometres (1,800 miles) in some cases. The focus is on 'dead' tectonic plates, pushed down to the bottom of the Earth's mantle and no longer part of the surface.

The Atlas has been produced through 15 years of work by the team from Utrecht University in the Netherlands, pulling together data from multiple sources as well as from their own seismic scans, using sound waves to measure the geological make-up of the ground.

"This is the first time that the slabs all over the world have been mapped," says one of the researchers, Wim Spakman. "Much of the information was already available, but mostly in the form of more or less isolated research projects. We have put all the pieces together, rather like a jigsaw."

Credit: Atlas of the Underworld

Credit: Atlas of the Underworld

As tectonic plates of crust and mantle shift on the surface of the Earth, they're causing volcanic activity and earthquakes, and sometimes triggering a process called subduction, where one plate is forced down into the Earth as it moves.

The part of the plates being subducted are then termed "slabs", as Spakman mentions above. These slabs can exist for millions of years without being melted by the heart of the Earth's core, and the new Atlas tracks 94 of them across the globe.

"Now we can trace not only how plates move over the surface, but how they sink to the core-mantle boundary," one of the team, Douwe van Hinsbergen, told Ryan F. Mandelbaum at Gizmodo. "That's the cool thing for me – we can learn about the physics inside the Earth."

The researchers have been able to tie slabs to their period of subduction, as well as to associated volcanic activity on the surface, or to mountain ranges still visible today, like the Andes or the Himalayas.

Not only is it an impressive catalogue of the subterranean world, the Atlas can also teach scientists about how the mantle works – the pressures and timescales and movements involved in this hidden underworld.

We can learn more about how the planet is evolving and how all of us living on the surface could be affected in the future: the Atlas has already been used to calculate CO2 emitted by volcanic activity, for instance, and how sea levels have changed over millions of years.

Through the Atlas, the scientists have also discovered a Slab Deceleration Zone some 1,500-2,000 kilometres (932-1,243 miles) below the surface, where slabs slow down but don't stop, before later accelerating towards the core.

And the team is hoping many more discoveries like this will happen in the future as the underworld map gets refined and expanded.

"Making an atlas is a long-term work of precision, and the end result may at first sight look like a coffee table book," says van Hinsbergen.

"But it should be remembered how often people use world atlases for purposes that never crossed the maker's mind. We expect the same to be true of the Atlas of the Underworld for geoscientists."

The research has been published in Tectonophysics.