Crustaceans might put up a hard exterior, but on the inside, they may be more sensitive than is often assumed.

For the first time, scientists have shown the brains of living shore crabs (Carcinus maenas) can process pain in nuanced ways, depending on the severity and location of the harm.

The discovery leaves open the possibility that crabs and related crustaceans really can experience pain. And while more research is needed, that means humans who boil or cut these creatures alive could be causing undue suffering.

"We need to find less painful ways to kill shellfish if we are to continue eating them," argues zoophysiologist Lynne Sneddon from the University of Gothenburg.

"Because now we have scientific evidence that they both experience and react to pain."

Scientists have long debated what it means to feel pain, and in recent years, some experts have argued that it's possible fish, amphibians, and octopuses respond to noxious stimuli at a cognitive level historically reserved for vertebrates.

Earlier this year, for instance, a study found that shore crabs showed signs of anxiety in the face of electric shocks and bright lights, learning to avoid the stimuli over time. This is consistent with predictions that crustaceans can experience pain. But some skeptical scientists have argued these are merely reflexes.

After all, even animals with basic nervous systems can respond to painful stimuli and learn to avoid them. That's a really important part of survival. But typically those responses are thought to be unconscious, triggered by the peripheral nervous system.

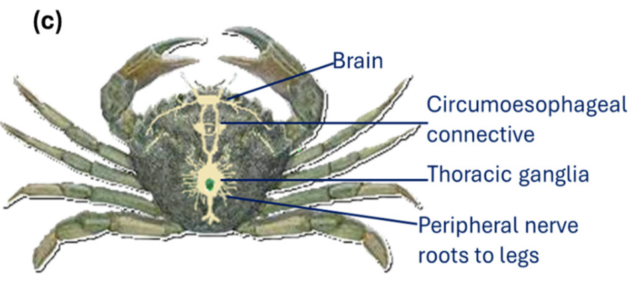

The 'conscious' recognition of harm requires integration from a centralized nervous system, and that is what researchers have now shown is possible in shore crabs.

The activity of the crab nervous system was monitored using an instrument similar to an electroencephalogram (EEG), which records electrical activity of the human brain from the skull.

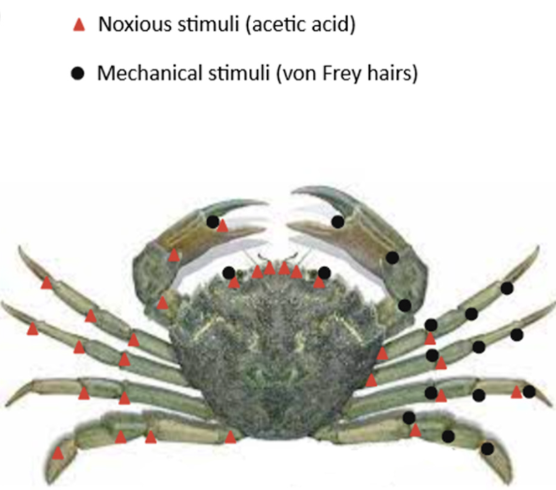

In this case, electrodes were placed on crab shells, and researchers began a standard pain test used on vertebrates and fish.

When a form of vinegar with varying acidity was smeared onto soft tissues around the body of several crabs, scientists could see pain receptors in the peripheral nervous system signaling parts of the brain.

The higher the concentration of acid, the greater the response from the crab's central nervous system.

When crabs were poked with a painful mechanical stimulus, instead of a chemical one, their central nervous system showed an even higher amplitude of electrical activity, albeit one that was coded in a different pattern.

In fact, researchers could tell just from the crab's brain activity whether it was processing the chemical stimuli or the mechanical one.

At this point, it's not clear whether the brain response from the mechanical prod was due to touch or pain.

Further studies are needed to clear up the details, but this is one of the first experiments to use electrophysiological signals to demonstrate pain-like responses across the body in a living crustacean.

The authors hope their findings can inform practices for animal welfare to ensure the least amount of suffering possible.

"It is a given that all animals need some kind of pain system to cope by avoiding danger. I don't think we need to test all species of crustaceans, as they have a similar structure and therefore similar nervous systems," says biologist Eleftherios Kasiouras from the University of Gothenburg.

"We can assume that shrimps, crayfish, and lobsters can also send external signals about painful stimuli to their brain which will process this information."

The study was published in Biology.