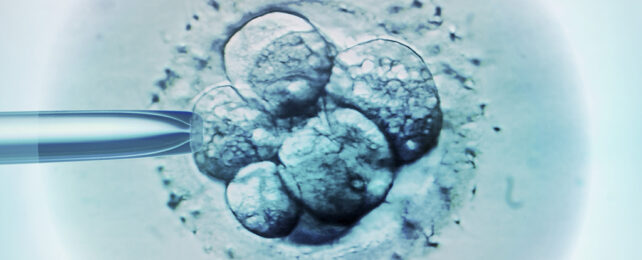

In a major scientific first, synthetic human embryo models have been grown in the lab, without any need for the usual natural ingredients of eggs and sperm.

The research – first brought to wider attention by The Guardian – has prompted excitement about the potential for new breakthroughs in health, genetics, and treating disease. But the science also raises serious ethical questions.

The embryo structures were produced from stem cells cultured from a traditional embryo in the lab. Stem cells can be programmed to develop into any kind of other cell – which is how they are used in the body for growth and repair.

Here, stem cells were carefully coaxed into becoming precursor cells that would eventually become the yolk sac, the placenta, and then the actual embryo itself.

A paper on the breakthrough has yet to be published, so we're still waiting on the details of exactly how this was achieved.

The work was led by biologist Magdalena Żernicka-Goetz, from the University of Cambridge in the UK, together with colleagues from the UK and US. Last year, a team led by Zernicka-Goetz was able to successfully grow synthetic mouse embryos with primitive brains and hearts.

We should point out that we're still a long way from creating babies artificially. These are embryo-like structures, without a heart or a brain: They're more like embryo models that are able to mimic some, but not all, of the features of a normal embryo.

"It is important to stress that these are not synthetic embryos, but embryo models," wrote Zernicka-Goetz on Twitter. "Our research isn't to create life, but to save it."

One of the ways in which this research could save lives is in helping to examine why many pregnancies fail at around the stage these artificial embryos replicate. If these earliest moments can be studied in a lab, we should get a much better understanding of them.

We could also use these techniques to learn more about how common genetic disorders develop at the earliest stages of life. Once there's a greater knowledge about how they start, we'll be better placed to do something about them.

At the same time, there are concerns around where this kind of synthetic embryo creation could lead. Scientists say strong regulations are needed to control this kind of research – regulations that at the moment don't really exist.

"These new assays in vitro will pave the way for future studies that aim to unravel the mechanisms of human development, as well as the effects of environmental and genetic anomalies," says biologist Rodrigo Suarez from the University of Queensland in Australia, who wasn't involved in the research.

"As with most emerging technologies, society will need to balance the evidence about the risks and benefits of this approach, and update the current legislation accordingly."

As pointed out by bioethics researcher Rachel Ankeny from the University of Adelaide, who wasn't involved in the research, today scientists abide by a '14-day rule' which limits the use of human embryos in the lab, requiring that human embryos can only be cultivated in vitro for a maximum of 2 weeks.

Rules like this, as well as new ones that may be brought in as this research continues, force us to ask fundamental questions about when we consider 'life' beginning in an organism's existence – and how close to a human embryo a synthetic embryo must be before it is considered essentially the same.

"We need to engage various publics about their understanding of and expectations from this sort of research, and more generally about their views on early human development," says Ankeny.

"These biological processes are deeply tied to our values and what we think counts as human life."

The research has yet to be peer-reviewed or published, and was presented at the annual meeting of the International Society for Stem Cell Research.