Researchers have developed a new kind of synthetic creature, using the heart cells of a rat to make a robotic stingray that follows light.

While the rat-ray hybrid certainly sounds like a bit of a Frankenstein mish-mash, it's serious research that could help pave the way for a greater understanding of how hearts pump blood around the body – in addition to leading to new kinds of more sophisticated synthetic robots.

The ray is the brainchild of bioengineer Kit Parker from the Wyss Institute at Harvard University, who was inspired to develop the cyborg after visiting an aquarium with his daughter.

"She was trying to pet a stingray and she put her hand in the water and the stingray quickly moved away from her hand in a very elegant way," Parker told George Dvorsky at Gizmodo. "It struck me like a thunderbolt that I could build that system in the musculature, and that it would look very much like the [muscular] layer of the heart."

Taking his idea to fellow Wyss researcher Sung-Jin Park, the ambitious project was met with more than a little trepidation at first.

"I sat down with him," Parker told Jon Hamilton at NPR, "and I said, 'Sung-Jin, we're going to take a rat apart; we're going to rebuild it as a stingray; and then we're going to use a light to guide it.' And the look on his face was both sorrow and horror."

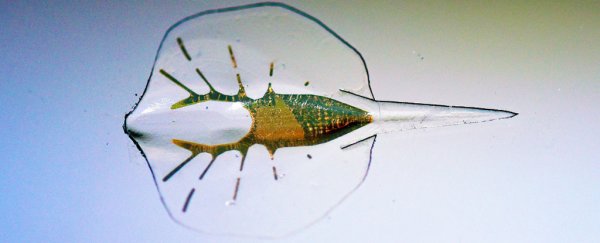

But with perseverance, the team succeeded in realising Parker's vision. The cyborg stingray, which weighs just 10 grams and is only about the size of a small coin, is made from a gold skeleton overlaid with a thin layer of stretchy polymer. This body, designed to emulate the shape and fins of a real ray, is coated in approximately 200,000 living rat heart cells, called cardiomyocytes.

These muscle cells were genetically engineered to respond to light cues, to prompt the fin movements that help propel the robot through water. When stimulated by light, the cardiomyocytes contract and push the fins downwards.

The design of the gold skeleton allows it to store some of this energy, releasing the fins in an upward motion before the cells contract again.

Even more impressive is the fact that, depending on the pulse and frequency of light shone at the synthetic creature, its direction and speed can be controlled, allowing it to navigate through the water and around obstacles.

The project, reported in Science, could offer some new leads for roboticists working with soft tissue structures, and also help marine biologists better understand how rays use their fins to swim.

But Parker's focus is on the cardiomyocytes – and how a better knowledge of the way heart muscles move might point to better synthetic pumps for use in humans, using a hybrid of organic tissue and mechanical elements.

The robotic ray beside a skate (Leucoraja erinacea). Credit: Karaghen Hudson

The robotic ray beside a skate (Leucoraja erinacea). Credit: Karaghen Hudson

"I want to build an artificial heart, but you're not going to go from zero to a whole heart overnight. This is a training exercise," Parker told NPR. "The heart's built the way it is for a reason. And we're trying to replicate as much of that function as we possibly can."

In the meantime, the researchers say they're done with their creation for now, and having learned what they have, won't be making any more. But given its unique combination of living and robotic parts, just how does the team itself classify their cyborg? As William Herkewitz at Popular Mechanics puts it to Parker, is this thing alive?

"I think we've got a biological life form here," Parker replied. "A machine, but a biological life form. I wouldn't call it an organism, because it can't reproduce, but it certainly is alive."

"We turned a rat into a light guided stingray," he added. "Hell, all [people] need to know is that this is the coolest thing they're going to see all year."