The world is direly addicted to plastics. Try as we might to recycle them, plastics are cheaper to make anew, so unthinkable amounts of plastic waste are dumped into landfill and are clogging up our oceans.

From all the new plastics ever made, over 6 billion metric tons of plastic waste (that doesn't decompose but only breaks up into smaller and small pieces) has been generated, with less than 10 percent recycled thus far.

Not only is manufacturing new plastics incredibly wasteful, but it uses starter materials derived from fossil fuels that need to stay in the ground if we want to avert climate change.

To make a small dent in that global problem, two materials scientists from Boise State University in the US have just developed a new kind of plastic that, unlike existing plastics, isn't made from crude oil and its derivatives.

What's more, small-scale lab experiments replicating industrial processes suggest roughly 93 percent of the new plastic could be recycled into clean starter materials – even when the plastic is mixed in with other unprocessed plastic waste, paper, and aluminum.

In their paper, Allison Christy and Scott Phillips describe making a new type of plastic based on poly(ethyl cyanoacrylate) or PECA, which is prepared from the monomer used to make Super Glue.

Like all plastic polymers, the new product is formed through a process of polymerization where single, repeating monomer units are strung together in a chemical reaction to make one long chain.

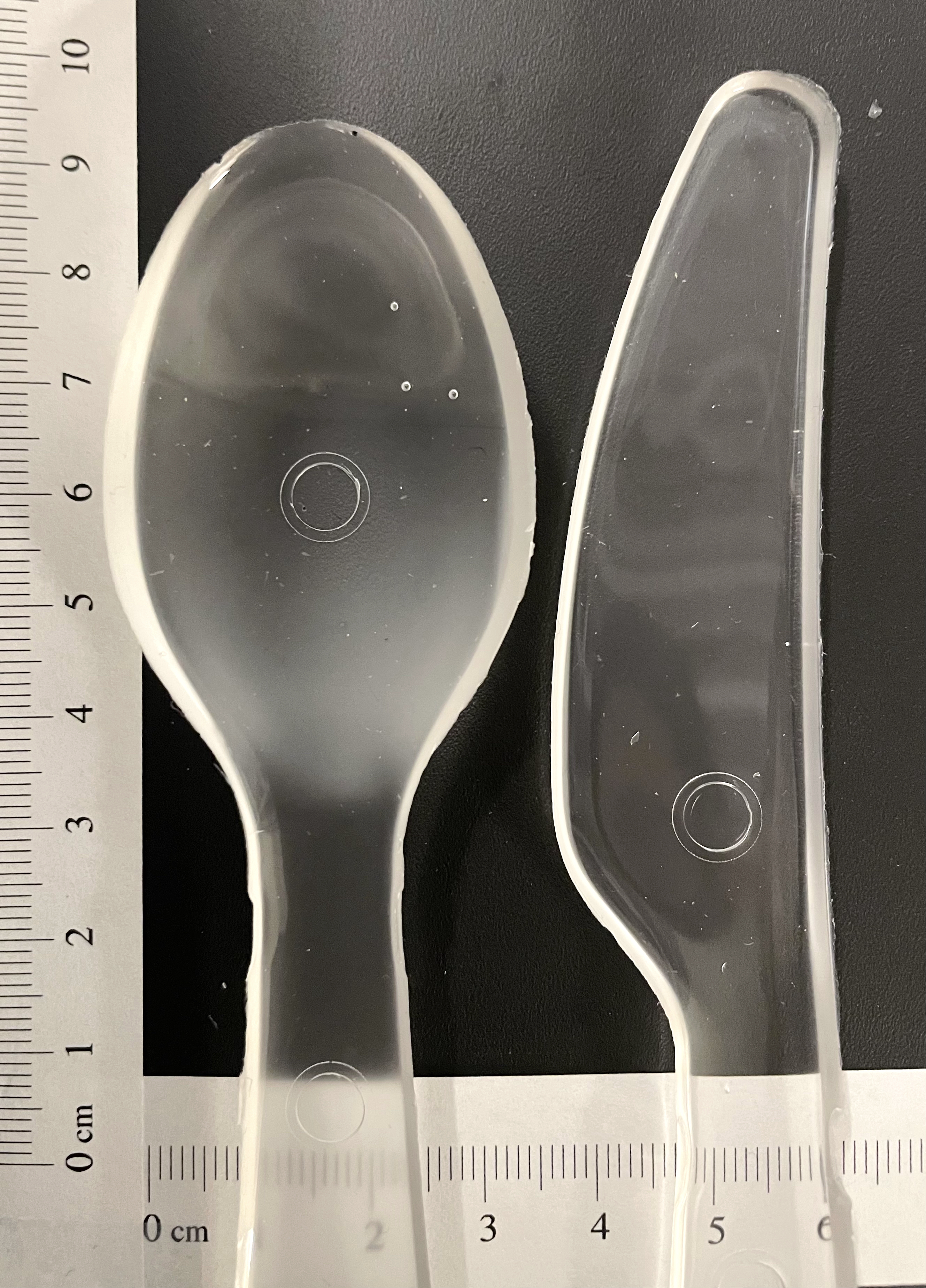

If manufactured at industrial scales, Christy and Phillips suggest their new, recyclable PECA plastic could replace polystyrene plastics that are not accepted in most curbside recycling programs.

Polystyrene plastics come in a few forms: expanded polystyrene, also known as Styrofoam, which is used as a lightweight packaging material or to make takeaway food containers; and thermally molded polystyrene, used to make disposable plates, cups, and cutlery.

While it would be great to replace these products with an easily recyclable alternative, polystyrene accounts for only 6 percent of current plastic waste, a small chunk of a much larger problem.

Christy and Phillips think, however, that in time, their new PECA plastic could offer a competitive alternative to other forms of plastic beyond polystyrene.

"Owing to the excellent materials properties and ease of recycling, PECA may be useful in other contexts other than simply replacing polystyrene, which would further improve the extent to which a plastic waste stream could be recycled," Christy and Phillips write in their paper.

All that remains to be tested. Initial lab experiments from Christy and Phillips suggest the new PECA plastic has comparable properties to existing plastics, and is stable in hot, humid environments.

This durability and resistance to degradation is what makes plastics so versatile but also difficult or impossible to destroy. Yet they contain the building blocks for new plastics, linked up in a neat row, if you find a way to disassemble them. But most plastics are either incinerated or discarded.

When it comes to recycling, Christy and Phillips showed how the long polymer chains of the PECA plastic can be thermally 'cracked' at temperatures of 210 °C and the resulting monomers distilled into a clean product to use again.

Recycling plastics is indeed a noble strategy, but the right systems need to be in place for consumers to get on board. Norway has made strides in implementing schemes that have seen 97 percent of plastic bottles recycled.

Meanwhile, a recent report from Greenpeace USA found that only about 5 percent of plastics are currently recycled in the United States, after China's recycling industry stopped taking other countries' plastic waste.

The bulk of that plastic waste can be traced back to a handful of global companies, leading some experts to argue that the onus is on those companies to develop suitable alternatives and cut down their production of single-use plastics to tackle the root cause of the world's waste crisis.

As a trio of scientists writing in the journal Science pointed out in 2017 after analyzing the production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made, recycling only reduces future plastic waste generation if – and only if – it displaces primary plastic production.

However, "this displacement is extremely difficult to establish."

The study has been published in Science Advances.