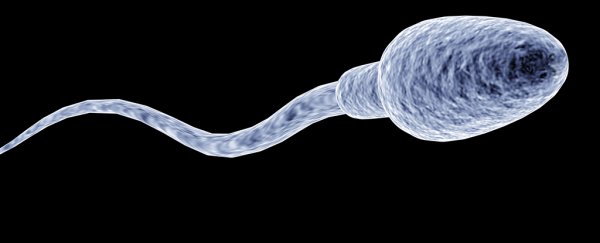

Our DNA is packed into our nucleus pretty damn tightly. Each chromosome is one looong DNA molecule wrapped around proteins called histones, like a very tiny thread on very tiny spools.

But sperm puts even the packing skills of chromosomes to shame.

"If DNA were to take up as much space as a watermelon under normal circumstances, sperm cells would then only be as big as a tennis ball," says University Hospital Bonn developmental researcher Hubert Schorle.

In humans and in mice, two proteins called protamines replace the histones to pack the DNA even more densely, making use of every bit of space like blocks in a game of Tetris. This process is called hypercondensation.

How this happens is fairly well understood, but Schorle and a team of researchers have dug even deeper into the process of hypercondensation and looked at what happens if you mess with one of those protamines, PRM2.

During the whole process of creating sperm, a part of the PRM2 protein called the N-terminus is cut off. This cutting off, or cleaving, seems to be critical to make sperm, well… sperm.

"Proper PRM2 cleaving therefore seems to be crucial for successful reproduction, yet, the function of the cleaved PRM2 domain and PRM2 processing are unknown to date," the team write in their paper.

To discover what happens, the researchers created mutant mice that didn't have an N-terminus on their PRM2 to remove. After closely inspecting their sperm, the team found that PRM2 definitely needs to be cut down to size, as the mice with uncleaved PRM2 had DNA that entirely fell apart.

"The removal of transition proteins during hypercondensation is impaired," says first author Lena Arévalo, also from the University Hospital Bonn.

"In addition, the condensation seems to proceed too quickly, causing the DNA strands to break."

This, quite unsurprisingly, led to infertile males, but only when both copies (or alleles) of PRM2 were lost or damaged. When just one of those genes was lost, the mice stayed fertile. You can see a diagram of this below.

(Arévalo et al., PLOS Genetics, 2022)

(Arévalo et al., PLOS Genetics, 2022)

Although we don't have any direct evidence of this action in humans yet, it's possible that human fertility issues could sometimes be caused by issues with PRM2 cleaving. The team is currently looking into if this is the case.

"There are only a few research groups that analyze the role of protamines in hypercondensation," says Schorle.

"We are the only laboratory in the world to date that has succeeded in generation and breeding of both PRM1 and PRM2 deficient mouse lines which are now used to study the role of these proteins in spermatogenesis."

The research has been published in PLOS Genetics.