Researchers in the US have turned taste on and off in mice simply by activating and silencing certain brain cells. This demonstrates for the first time that taste is hardwired in the brain, and not dictated by our tastebuds, flipping our previous understanding of how taste works on its head.

It was previously thought that the taste receptors on our tongue perceived the five basic tastes – sweet, salty, sour, bitter, and umami – and then passed these messages onto our brain, where it registered what we'd just tasted. But the new study shows that although our tongues do detect the presence of certain chemicals, it's our brains that perceive flavour.

"Taste, the way you and I think of it, is ultimately in the brain," said lead researcher Charles S. Zuker from Columbia University Medical Centre. "Dedicated taste receptors in the tongue detect sweet or bitter and so on, but it's the brain that affords meaning to these chemicals."

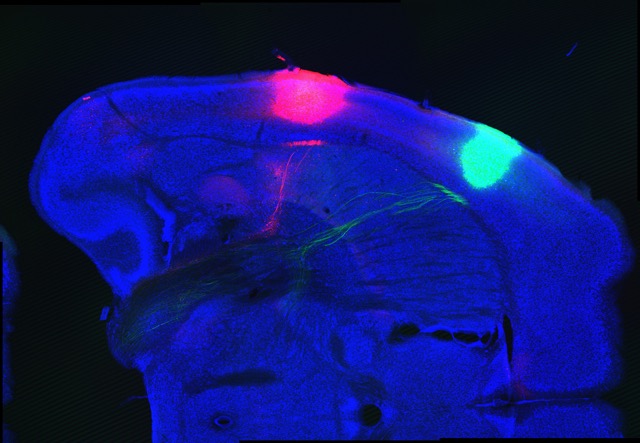

Previous work by Zuker's lab discovered that our tongue has dedicated receptors for each taste, and that each class of receptors sends a specific signal to the brain. More recently, the team built on this by showing that in addition to dedicated receptors, there are unique sets of brain cells – each in different locations – that receive these signals. The red area below is the bitter neurons, and the aqua shows where the sweet brain cells are.

Charles Zucker/Columbia University Medical Centre

Charles Zucker/Columbia University Medical Centre

In this study, they decided to play with these brain cells and see if they could activate or deactivate them in order to trick mice into thinking they were tasting something sweet or bitter, without them actually tasting either.

"In this study, we wanted to know if specific regions in the brain really represent sweet and bitter. If they do, silencing these regions would prevent the animal from tasting sweet or bitter, no matter how much we gave them," said Zuker. "And if we activate these fields, they should taste bitter or sweet, even though they're only getting plain water."

What they observed was exactly as they'd expected – when the sweet neurons were silenced using an injectable drug, the mice couldn't taste anything sweet, but they could still detect bitter flavours.

And when the researchers activated the sweet neurons using laser light, the mice tasted sweet flavours, even though they were only drinking plain water. The same thing happened when they stimulated or silenced the bitter brain cells.

The team was able to tell what the mice were tasting by their obvious reactions – they licked their lips when they tasted real or simulated sweet flavours, and gagged and looked disgusted when they tasted bitter.

To make sure what they were seeing was real, the researchers trained mice to perform certain behaviours when they tasted something sweet or bitter, and their behaviours didn't differ between the real and simulated tastes. The same thing even happened in animals that had never tasted either of the flavours before.

"These experiments formally prove that the sense of taste is completely hardwired, independent of learning or experience," said Zuker.

This discovery not only changes everything we knew about taste, but demonstrates that taste is different from the olfactory system because it's hardwired.

"Odours don't carry innate meaning until you associate them with experiences. One smell could be great for you and horrible to me," added Zuker. But taste is already set. "In other words, taste is all in the brain."

The research has been published in Nature.