Right now, about 70 percent of our discarded electronics end up in landfill, amounting to a record-breaking 41.8 million tonnes of e-waste dumped around the world last year. And not only is this huge build-up a complete waste of space, all of those discarded electronics are constantly leaking dangerous levels of toxic chemicals into the surrounding environment.

So researchers in the US are developing something that just might put a dent in that colossal amount of e-waste - a high-performance semiconductor chip made almost entirely out of wood. "The majority of material in a chip is support. We only use less than a couple of micrometers for everything else," one of the team, engineer Zhenqiang Ma from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, said in a press release. "Now the chips are so safe you can put them in the forest and fungus will degrade it. They become as safe as fertiliser."

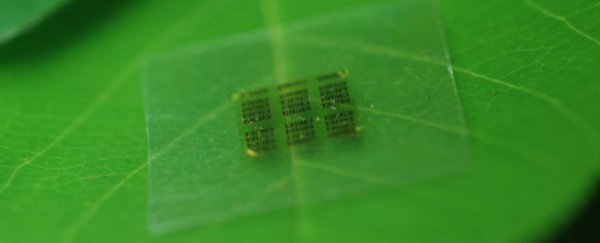

The chip works by having its normal support layer replaced by a flexible and biodegradable layer of cellulose nanofibril (CNF) - a strong and transparent material that's derived from wood when you break it down to its nanoscale fibres.

Ma and his team have spent over a decade trying to figure out how to get the surface of a biodegradeabe material smooth enough to work as a support layer for the chip, and with the capacity for thermal expansion. They found that CNF worked the best for this over the petroleum-based polymers they tried.

"You don't want it to expand or shrink too much. Wood is a natural hydroscopic material and could attract moisture from the air and expand," one of the team, Shaoqin Gong said. "With an epoxy coating on the surface of the CNF, we solved both the surface smoothness and the moisture barrier."

The team's next challenge was to show that even a wood-based chip could perform just as well as existing gallium arsenide-based microwave chips - one of the most commonly used chips in consumer electronics. So far, it's looking good.

"I've made 1,500 gallium arsenide transistors in a 5-by-6 millimetre chip," says one of the team, Yei Hwan Jung, said in the release. "Typically for a microwave chip that size, there are only eight to 40 transistors. The rest of the area is just wasted. We take our design and put it on CNF using 'deterministic assembly technique', then we can put it wherever we want and make a completely functional circuit with performance comparable to existing chips."

Publishing in Nature Communications, the team says it's this flexibility, and the fact that it's completely biodegradable, that they hope will make it an attractive option for electronics companies in the future. "Mass-producing current semiconductor chips is so cheap, and it may take time for the industry to adapt to our design," said Ma. "But flexible electronics are the future, and we think we're going to be well ahead of the curve."