Mammal mothers give up a lot to care for their young. To nourish their newborns with milk, their bodies pull calcium from their very own bones.

Scientists have long wondered why mothers' skeletons don't crumple under the pressure, and US researchers led by the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) think they have solved the mystery.

The team has discovered a whole new hormone in female mice that promotes the growth of astonishingly strong and dense bones.

Neuroscientists have named it the maternal brain hormone (MBH), though it works to build strong and healthy bones in mice of all ages and sexes.

"One of the remarkable things about these findings is that if we hadn't been studying female mice, which unfortunately is the norm in biomedical research, then we could have completely missed out on this finding," says pharmacologist Holly Ingraham, who is head of her own lab at UCSF.

"It underscores just how important it is to look at both male and female animals across the lifespan to get a full understanding of biology."

Today, male brains have been the focus of the vast majority of brain research, and only 2 percent of published neuroimaging studies have examined hormonal factors, like sex steroids.

Estrogen is a bone-building sex steroid with widespread impacts on the brain. While it rises and falls throughout life, estrogen is produced in lower quantities after menopause, leaving older women vulnerable to the bone-weakening effects of osteoporosis.

Estrogen levels drop when a person is breastfeeding as well, which also slows bone growth. Meanwhile, the mother's body leeches or 'resorbs' calcium from the skeleton to continue feeding their newborn, which ought to further put bones at risk.

In 2019, Ingraham's lab at UCSF were surprised to find that when estrogen was blocked from a specific part of the female mouse brain, it actually improved the animal's bone strength significantly.

It seemed that some other bone-building hormone was replacing the estrogen, and now researchers have found it.

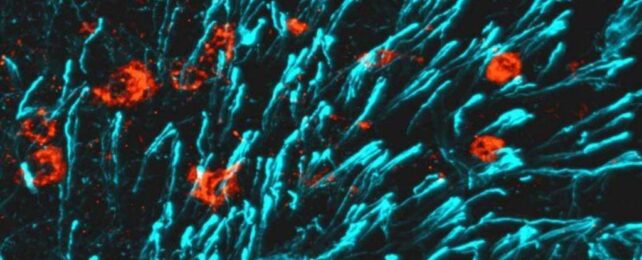

The maternal brain hormone, or MBH, is a known protein called CCN3. Secreted by neurons in a part of the brain called the arcuate nucleus, it is involved in reproduction and puberty.

During normal lactation in mice, the production of MBH from these neurons surges as estrogen falls.

MBH was found to stimulate stem cell activity in mouse and human bone tissue in the lab. In living mice of all ages and sexes, a rise in MBH boosted bone remodeling and accelerated fracture repair.

This is particularly important for female mice. Feeding a large litter of newborns requires a rodent mother to sacrifice nearly 30 percent of her bone density.

Even though the losses normalize when lactation stops and estrogen surges once again, the mother and her pups would fare poorly without the counteracting nature of MBH. In experiments on living mice, when MBH production was artificially inhibited, researchers found the mother lost far more bone density than is typical and the pups rapidly lost weight.

By contrast, when researchers introduced extra MBH into young adult and old mice, both male and female, the animals showed huge increases in bone mass and strength within weeks.

For older female mice with very low estrogen levels, MBH treatment more than doubled their bone mass.

"There are some situations where highly mineralized bones are not better; they can be weaker and actually break more easily," says stem cell biologist Thomas Ambrosi from University of California Davis.

"But when we tested these bones, they turned out to be much stronger than usual. We've never been able to achieve this kind of mineralization and healing outcome with any other strategy."

That's not the last of the good news, either. When researchers packaged MBH into a hydrogel patch and applied it directly onto a fractured bone in an older mouse, it promoted bone growth at the site of the fracture.

Further research is now needed to figure out how well these results translate to humans. When breastfeeding, humans temporarily lose about 10 percent of their bone density, which is significantly less than in mice.

"Bone loss happens not only in post-menopausal women but often occurs in breast cancer survivors that take certain hormone blockers; in younger, highly trained elite female athletes; and in older men whose relative survival rate is poorer than women after a hip fracture," explains Ingraham.

"It would be incredibly exciting if [MBH] could increase bone mass in all these scenarios."

The study was published in Nature.