For most humans who have breathed Earth's air over the course of history, our deaths have disappeared from record, as completely as an exhalation.

For one resident of the ancient Roman Empire, who met a violent demise around 1,800 years ago, archaeologists have found the first record of its kind scarred into his bones: he was mauled by a lion, probably in gladiatorial combat.

No other gladiatorial remains have ever been recovered bearing the marks of animal conflict.

What makes the discovery even more spectacular is where he was found: the Roman-era cemetery of Driffield Terrace in York, England – far from the center of the Roman web.

Historical records state that lions were set to work in the gladiatorial arena. Now, the bones prove it happened, not just in Italy, but in some of the farther reaches of the empire, verifying suspicions that the Driffield Terrace cemetery was for the interment of fallen arena fighters.

"The bite marks were likely made by a lion," says archaeologist Malin Holst of the University of York in the UK, "which confirms that the skeletons buried at the cemetery were gladiators, rather than soldiers or slaves, as initially thought and represent the first osteological confirmation of human interaction with large carnivores in a combat or entertainment setting in the Roman world."

The Roman Empire is remarkably well understood based on contemporaneous record-keeping as well as artworks and other cultural artifacts that survived the ravages of time for us to collect and pore over, long after the empire itself fell.

We know, therefore, that gladiators were a popular spectacle, with human fighters entering vicious combat both with each other, and large carnivorous animals such as bears and lions.

However, the remains of actual arena fighters – their bones – are almost vanishingly rare, making it difficult for archaeologists to verify the reports with hard evidence.

When the remains of 74 well-built adult men from Roman-era Britain were discovered in York in excavations that took place in 2004 and 2005, scientists were thrilled. The discovery represented a possible trove of gladiatorial remains to provide context to history.

These remains are fascinating. Some had been cremated, and a large number of the skeletons (at least, those complete enough to tell) had been decapitated, from back to front in the manner of an execution.

The graves were shallow, and contained no grave goods or markers. One skeleton had large iron rings around his ankles, and the number of healed or healing injuries was high. Isotopic analysis also suggested that the men had come from many different places.

There were several theories, the researchers report, including a massacre, a soldiers' cemetery, or a burial pit for slaves. One similarity, however, drew their attention: the healed cranial injuries were very similar to those seen in a gladiatorial burial site at Ephesus.

So here we had a cemetery filled with the bodies of robust men, who were geographically diverse in origin, who repeatedly engaged in combat-like activities, and many of whom had been decapitated, as gladiators reportedly sometimes were after death. Hmmmmmm.

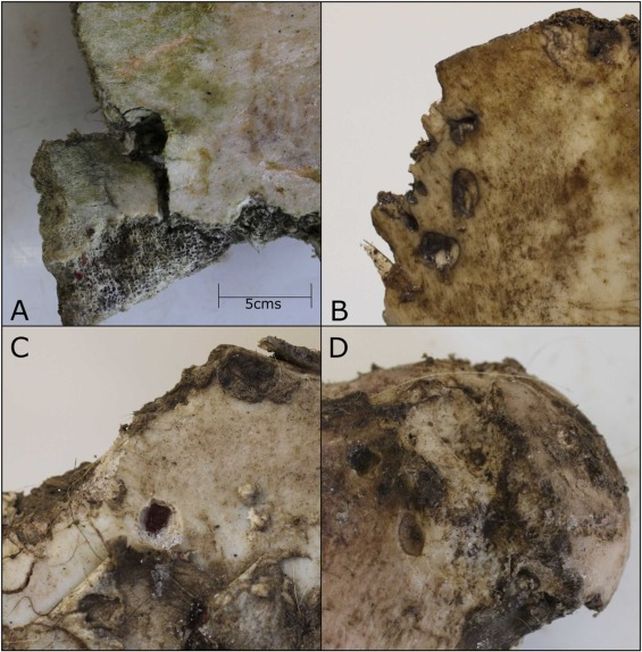

Then we get to an individual named 6DT19. He was buried in a box with several other individuals, decapitated of course. But his bones had something unique: puncture marks and scored furrows on the pelvis.

Led by anthropologist Tim Thompson of Maynooth University in Ireland, a team of scientists took 3D scans of the bones to try and understand what had made the marks. They compared the marks to reports of how animals attack humans, and the bite patterns of felines, canines, and bears.

After an exhaustive comparison, the team concluded that the marks were most likely made by a large feline, such as a lion. The marks show no signs of healing, which means they occurred around the time of death, and they appear to be consistent, not with an attack, but with the big cat settling in for a bite to eat.

"The implications of our multidisciplinary study are huge. Here we have physical evidence for the spectacle of the Roman Empire and the dangerous gladiatorial combat on show," Thompson says.

"For years, our understanding of Roman gladiatorial combat and animal spectacles has relied heavily on historical texts and artistic depictions," explains Thompson.

"This discovery provides the first direct, physical evidence that such events took place in this period, reshaping our perception of Roman entertainment culture in the region."

The researchers determined that the man was aged between 26 and 35 when he died, around 200 to 300 CE. He appears to have suffered from childhood malnutrition, as well as back problems from carrying too much weight.

The team believes he may have been a type of Bestiarius, a volunteer arena fighter who fought animals rather than other men. This implies that exotic animals were possibly transported to York for the entertainment arena. There may even have been an amphitheater there, although no traces of one have been found.

Nevertheless, the discovery is a rare, crystal-clear glimpse into a world long gone.

"This latest research gives us a remarkable insight into the life – and death – of this particular individual," says archaeologist David Jennings, CEO of York Archaeology.

"We may never know what brought this man to the arena where we believe he may have been fighting for the entertainment of others, but it is remarkable that the first osteo-archaeological evidence for this kind of gladiatorial combat has been found so far from the Colosseum of Rome."

The research has been published in PLOS ONE.