The answer to the question 'how much sleep do I need each night?' depends on a variety of factors, and we just found a new one: a rare mutation in the SIK3 gene that seems to enable the brain to function on less sleep than normal.

Led by a team from the Chinese Academy of Sciences, researchers found the mutation in a healthy woman in her 70s, who slept an average of 6.3 hours per night. This was part of a wider project to identify people matching a natural short sleeper (NSS) profile.

This is actually the fifth short-sleep genetic mutation that's been identified, further highlighting the influence of our genetics on sleep health, and the amount of slumber we need to function properly.

"Studying human sleep genes not only expands our knowledge regarding the sleep regulatory network, but also may bring the basic research from mouse models to clinical relevance," write the researchers in their published paper.

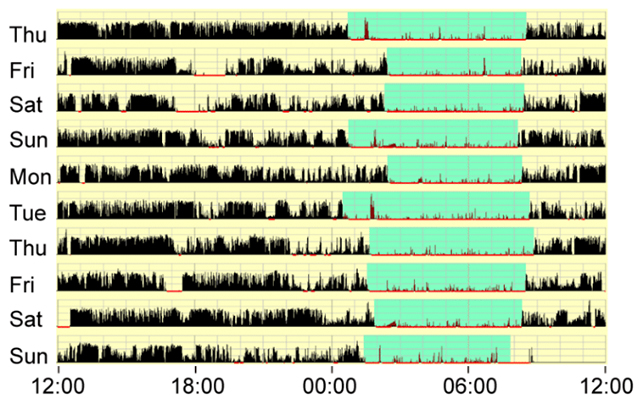

Mice engineered with the same genetic mutation also slept less, the researchers found, though not by much: these animals typically snooze for around 12 hours each day, and the genetic editing reduced this by around half an hour.

Scans of brain activity in the mice showed that the proteins produced by the mutated gene were active across the synapses connecting neurons together.

We already know that SIK3 produces what's called a kinase protein, which sends chemical signals to other proteins to change their function. It seems some of that signaling is involved in regulating how long we need to be asleep for.

"These findings advance our understanding of the genetic underpinnings of sleep, highlight the broader implications of kinase activity in sleep regulation across species, and provide further support for potential therapeutic strategies to enhance sleep efficiency," write the researchers.

Those "potential therapeutic strategies" could involve the development of drugs to deal with sleep disorders. That's still a long way off, but each study gets us a little closer.

The discovery of genetic mutations like this, and the NSS individuals who are affected by them, also gives us more pointers for what the brain is actually doing during sleep: keeping the immune system in good condition, making sure our cognitive abilities stay sharp, and sorting through the events of the day.

"These [NSS] people, all these functions our bodies are doing while we are sleeping, they can just perform at a higher level than we can," neuroscientist and geneticist Ying-Hui Fu, from the University of California, San Francisco, told Freda Kreier at Nature.

The research has been published in PNAS.